USS Fletcher (DD 445) of the 175-ship 2,100-ton Fletcher class was an outstanding example of promise fulfilled. Completed in June 1942, she arrived at Guadalcanal in October and soon proved herself during a vital time when the US Navy’s posture in the Pacific war was changing from defensive to offensive, an auspicious beginning to a 27-year career.

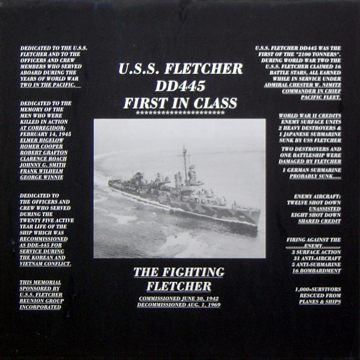

Memorial Wall plaque

National Museum of the Pacific War,

Fredericksburg, Texas.

Named for World War I-era Atlantic Fleet commander Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, Fletcher had been laid down side-by-side with Radford at strike-plagued Federal Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., Kearny, NJ, on 2 October 1941, by which time 22 sisters had been under construction for as many as seven months.

Federal launched the two plus 1,630-tonners Mervine and Quick in a single eventful day, 3 May 1942, and commissioned Fletcher a very short 58 days later, 30 June, only the third ship of the class (after Bath-built Nicholas and O’Bannon) to join the fleet.

Fletcher went to war under Cdr. William M. Cole and his exec, LCdr. Joseph C. Wylie, a “great team” who trained the crew rapidly. Arriving in the Solomon Islands in October, the “Fighting Fletcher” (whose hull numbers’ sum is 13) was the 13th in line with Task Force 67 (sum=13) at the “Friday the 13th” of November Battle of Guadalcanal, from which she emerged without damage and from which her crew derived the nickname “Lucky 13.”

A contributing factor was the first combat application of what came to be known as the CIC—the “combat information center,” a joint innovation of Cole and Wylie, whose battle station was the PPI (SG radar) scope in the chart house. From there he could speak the captain a few feet away on the bridge, keeping him continuously advised of the tactical situation, selecting targets and directing gun and torpedo control. “The effectiveness of the Fletcher’s engagement was due principally to his intelligent analysis and cool judgment,” wrote Capt. Cole in his action report.

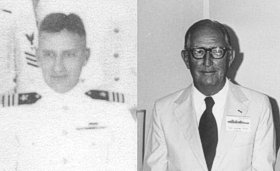

RAdm. Cole in 1942 and 1980.

We had the best skipper and exec in the Navy,” remembers then-Ens. Fred Gressard. “Capt. Cole was a wonderful person, beloved by the entire crew, who had a marvelous relationship with XO Wylie. They were two of the best officers I ever met … ” (continued)

RAdm. Wylie in 1942 and 1992.

The Navy learned immediately. At the Battle of Tassafaronga in the same waters two weeks later, she was stationed not last in line but first, with Capt. Cole commanding the van destroyers—Perkins, Maury and Drayton. These he maneuvered “with skill and determination” in a “nearly perfect torpedo attack,” engaging the enemy with guns until he had no more targets, disengaging as instructed and circling back at high speed to reengage. On discovering the enemy had retired, he then set to rescuing 646 survivors of torpedoed cruiser Northampton, CA 26, whose grateful crew continued to attend Fletcher reunions over the following decades (Drayton also picked up 127 officers and men).

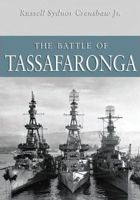

Unfortunately, credit for Cole’s and Wylie’s accomplishment was denied at the time. As detailed in Capt. Russell S. Crenshaw, Jr.’s 1995 book The Battle of Tassafaronga, the van destroyers’ torpedo attack was thwarted by the interference of Task Force commander Admiral Carleton Wright, who withheld permission to fire for a critical five minutes while targets passed obliviously by; then opened gunfire, alerting them before giving the torpedoes opportunity to hit. In addition to Northampton’s loss, three other heavy cruisers were damaged and in the furor, “Admirals Halsey and Nimitz … ended in heaping criticism on the only subordinate who had used his weapons to their maximum capability, and who handled his ships with both skill and determination, bringing them through the long night unscathed”—Cdr. Cole. It was one of Halsey’s lowest moments in Crenshaw’s view—Halsey, an old destroyerman, thinking in terms of gunnery only—but more than four decades later, his own book finally gave Cole recognition for his handling of the van destroyers—“one of the bright lights of that difficult time.”

Capt. Russell S. Crenshaw, Jr.’s book The Battle of Tassafaronga, an insightful analysis vindicating Fletcher by Capt. Russell Crenshaw, Jr.

Fortunately, someone else did react. Relieved as Fletcher’s commanding officer less than two weeks after Tassafaronga, Cdr. Cole became the first commanding officer of Destroyer Division 44 in Destroyer Squadron 22, assigned in March 1943 to operate with RAdm. A. S. Merrill’s cruisers. Commanding DesRon 22’s other division, DesDiv 43, was Cdr. Arleigh Burke, newly-arrived from Washington, who set out to learn destroyer tactics by studying the Battle of Tassafaronga in particular. In time, he proposed to Adm. Merrill a doctrine of independent destroyer operations, which was applied with success by Cdr. Frederick Moosbrugger at the Battle of Vella Gulf, by Burke himself at the Battles of Empress Augusta Bay and Cape St. George, and finally on a grand scale at the Battle of Surigao Strait—the winning tactic in World War II nighttime surface warfare.

On 1 February, De Haven was sunk in an air attack while returning from a mission with Nicholas and landing craft. Fletcher, nearby on a similar mission, joined in rescuing her survivors in Guadalcanal’s Ironbottom Bay, not far from where Northampton had been lost. Later that month, the striking force participated in the occupation of the Russell Islands and, in early March, another Munda bombardment.

The surface navy was reorganized into numbered fleets in mid-March and Destroyer Squadron 21 formed under Capt. Francis X. McInerney. Within the squadron, Fletcher and Federal-built sisters Radford and Jenkins were assigned to Division 42 with Taylor substituting for the damaged La Vallette. From then into July, the squadron operated with Cruiser Division 9 under RAdm. Walden L. Ainsworth in preparing for the forthcoming New Georgia operation, bombarding Munda again in May.

On 10 June, however, an engineering casualty disabled Fletcher’s starboard engine. With her screw removed, she returned via Pearl Harbor to Mare Island, where she was under repair 9 July–13 August while her 40mm armament was also brought up to date. Having thus missed the New Georgia operation, Fletcher arrived back in the South Pacific in late September and rejoined her division (now with La Vallette) at Éfaté in October.

Her second tour was a short one, however. Battle-worn Squadron 21 was ordered home for overhaul at the beginning of November, pausing to support the invasions of Tarawa and Kwajalein in the Gilbert Islands en route. Making San Francisco Bay 15 December with Radford, Jenkins, La Vallette, Nicholas and Taylor, Fletcher received a minor refit at Oakland and then was stationed at San Diego. Like other ships in her squadron, now including Hopewell, she departed in mid-January 1944 to resume support of the Marshall Islands operation; then was assigned to the Seventh Fleet, supporting Gen. MacArthur’s jungle campaign along New Guinea’s north coast to Morotai from Milne Bay, Manus (Seeadler Harbor) in the Admiralty Islands and Hollandia (Humboldt Bay).

The otherwise-quiet New Guinea operation featured one notable surface engagement: the “Battle off Biak” on 9 June. Under the tactical command of Australian RAdm. Crutchley, Fletcher led her division—with other destroyers and cruisers following—in a 35-knot nighttime pursuit of five Japanese destroyers attempting a reinforcement run. As they gradually overhauled the enemy and exchanged fire, destroyer Shiratsuyu was hit and temporarily slowed but not stopped. Return fire concentrated on Fletcher but scored no hits before the division broke off the chase to avoid risking friendly aircraft or submarine attack.

Still with the Seventh Fleet, Fletcher was not present for the invasion of Leyte in October, but arrived with a supply echelon on 23 November. Operating from San Pedro with Nicholas, O’Bannon and La Vallette on 6–7 December, she participated in a sweep and shore bombardment at Ormoc Bay on Leyte’s west coast, part of a hazardous multi-day operation in which Cooper, Mahan, Ward and Reid were lost.

Fletcher next moved with her squadron to patrol under kamikaze threat in the vicinity of Mindoro in support of the landings at Lingayen Gulf in January 1945. As soon as Subic Bay was secured as a base, the squadron began operating from there against the defenses of Manila Bay a few hours’ steaming down the Luzon coast.

On 14 February (the same day that La Vallette and Radford were mined in nearby Mariveles Harbor), Fletcher and Hopewell were drawing fire from concealed enemy positions on Corregidor when both were hit by 6-inch shore batteries. Fletcher was easily repaired, however, and continued to operate with her squadron over the next months, attached to VAdm. Daniel E. Barbey’s Seventh Fleet Amphibious Force for the liberation of Palawan and Zamboanga by mid-March.

In April, VII ’Phib closed Borneo for the war’s last amphibious landing at Tarakan. There, on the 30th, Jenkins—Fletcher’s sole remaining operational division mate—also struck a mine. Fletcher escorted her at 5 knots toward Subic Bay until relieved by Hart on 5 May; then took aboard her wounded and returned to the west coast via Leyte, Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor. After overhaul at Bethlehem Steel, San Pedro, CA, Fletcher again moved to San Diego, where she was stationed when the war ended.

Like her surviving DesRon 21 sisters, Fletcher was placed in reserve; then recommissioned as an escort destroyer (DDE) in 1949. She served through the fifties and sixties off Korea and Vietnam, attached to the same division in the Pearl Harbor-based “Pineapple Fleet” as Nicholas, with which she shared a formal 25th anniversary celebration in 1967. On 1 October 1968 she was transferred from DesRon 25 to replace Philip in DesRon 11 for one last WestPac cruise with a mix of Philip and Fletcher shipmates on board.

Among World War II US Navy destroyer candidates for preservation, Fletcher’s standing as class leader, fine record (including 15 World War II battle stars, a number surpassed by few other ships) and longevity were self-recommending and after she decommissioned and was stricken in 1969, plans were made to restore her as a museum ship. These fell through, however, and she was sold for scrap in 1972.

Sources: Crenshaw, Russell S., Jr., The Battle of Tassafaronga, Nautical & Aviation Publishing, Baltimore 1995; private conversations with Capt. Crenshaw, Fletcher officers Dave Davenport, Don Sinclair and Fred Gressard; O’Bannon shipmate Ernie Herr, Office of Naval Intelligence combat narratives; USS Fletcher Action Reports, Morison.