Nate Cook, 2004. Also by Nate Cook on this web site: first person account from World War II including a “tour” of Newcomb, action at the Battle of Surigao Strait and multiple Kamikaze hits off Okinawa.

During those two years I had ample opportunity to observe her handling and steering characteristics.

Quartermasters are supposed to be good helmsmen, so I spent many, many hours steering her in all types of weather. Now, some 60 years later, I would like to give you some idea of how a Fletcher behaved. First I would like to describe the steering apparatus and then discuss the steering process. Know that this is all extracted from old memory and is therefore subject to error; but I will do my best.

The Newcomb had three “steering stations”:

At Norfolk I had been instructed in the intricacies of the steering engine system. So, for many months after commissioning my “Special Sea Detail” station (entering port, docking, anchoring, going through the Panama Canal, etc.) was in the SER, and I gained first-hand knowledge of the system. You all know how popular rack and pinion steering has become in automobiles. Well, the Fletchers had rack and pinion steering! The Newcomb had a single rudder, amidships. The rudder post, (a steel shaft perhaps ten inches in diameter) extended up into the SER, and had a large segment of a gear attached (the pinion). A straight “gear,” the rack, was attached to a double ended hydraulic piston perhaps four to five inches in diameter and perhaps ten feet long. The mating hydraulic cylinders were on both port and starboard sides. Thus, oil pumped into one cylinder moved the rudder in one direction and vice versa. Hydraulic pressure was provided by two pairs of electric motors driving hydraulic (wobble-plate) pumps. The two sets were for redundancy and were periodically alternated. Right in front of the steering engine was a gyro repeater and a ship’s wheel, just like the one on the bridge (except the helmsman faced aft). When the motors were working it was easy to steer from the SER getting courses by phone from the bridge. When electrical power failed, however, it was a different story. At Special Sea Details there were five men assigned to the SER. I was there to steer and the other four provided power by turning hand cranks which rotated the pumps; two men cranking while two rested. I would guess that each of the electric motors could output about a horsepower. Two men cranking could provide only a fraction of that. Under normal circumstances it took perhaps 5–10 seconds (pure guess) to move the rudder from one side to the other. Under manual control it took much longer. Therein lies a tale:

The Newcomb, after sea trials in the Boston area, left for her shakedown cruise to Bermuda. This was in December when the Atlantic is apt to be angry. Just off Boston we hit a significant storm resulting in perhaps 90% of the entire crew being seasick (I was not among the lucky 10%). Waves continuously swept over the main deck from bow to stern. Some of this water found a leak in the air intake for the SER and a lot of cold Atlantic water came down into the SER, shorting out the electrical power distribution box, and thus knocking out the steering engine. The call came over the PA: “Set special sea details in the SER.” So the four crankers and I spent seemingly forever down there (probably only 6–8 hours) trying to steer the ship in heavy weather. The SER is very small, perhaps ten feet square. There was no ventilation, and cold Atlantic water, into which several of us had been sick, was sloshing on deck. We tried our best to steer the ship, and I guess our general direction was toward Bermuda, but that was not a good show. So much for the steering engine!

The Fletchers were very narrow ships, about 376 feet long and 39 feet wide. From above they showed the aspect ratio of a cigar. One might think that, being long and slim, they would like to move in a straight line. Such was not always the case. The lovely Lady had a mind of her own and sometimes it defied reason to determine why she wandered so far off course. To be a good helmsman required very sensitive physical senses and a keen mind. It is necessary to predict what she is about to do in the next several seconds and take immediate corrective action. Once she starts to slide off course the rudder cannot be moved quickly enough to avoid wandering. So the helmsman tries to second guess the Lady.

The state of the seas have a strong effect on steering. Perhaps the worst condition is when the seas are from abaft the beam, on either quarter (following seas). Under these conditions an approaching swell will first lift the stern; then as the bow buries itself, the stern will tend to slide off to one side or the other (the precursor to broaching in a very heavy sea), and the ship will soon be 5, 10, or 15 degrees off course—not a happy situation. In trying to bring her back on course, the helmsman can easily apply too much rudder, overcompensating, and, due to the side thrust on the rudder, causing the ship to roll. When this happens at mealtime, on a calm day, but with swells from astern, down in the mess-hall you will hear loudly “Who the Hell is on the wheel?”

To avoid this situation requires an intimate relation between the Lady and the helmsman. Using information due to any shift of weight on his feet, from his inner ear, his visual reference, and propiocentric inputs from his various joints, plus “gut” feelings, he will, over time, learn how to handle the Lady—most of the time! Under almost any condition a destroyer will roll, so amid considerable general movement you must be sensitive to just the right signals—the “signal to noise ratio” is not high!

Fueling at sea.

Roger Hanson was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for suggesting to Capt. Cook, in the midst of our 38-knot retirement from our torpedo attack on the battleship Yamashiro during the Battle of Surigao Strait, that he, Roger, zig-zag to confuse the ships firing on us. He did and we were not hit!

An aside: Some 30 years later, after I had become a Full Professor at M.I.T., then-Admiral Libby and I had some very good interactions.

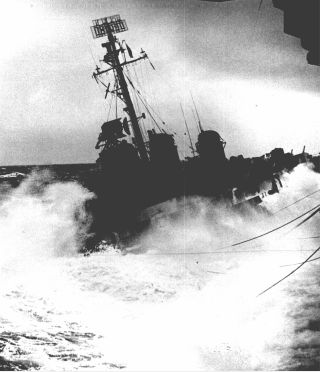

Perhaps the most difficult steering situation is while steaming alongside another ship to transfer mail, personnel, or fuel. We frequently refueled at sea from fleet oilers or from other men of war. The other ship was always huge compared to the Newcomb; and to steam alongside at perhaps 15 knots and a distance of 40 feet is enough to give any helmsman ulcers! This is a job for the stout-hearted as can be seen in the photo at right. If the ships get too far apart during fueling, the hoses will part, causing a substantial mess and a great many four letter words directed at the helmsman. While transferring personnel via a breeches buoy, if the ships come too close, then someone will get a dunking. But worst of all is getting too close while transferring mail. A man easily survives a bit of dunking, letters seldom do!