Charlie Greco in 1943 and 2003.

Shortly after December 7th, a lot of guys on the block went to join the service, so I went to enlist in the Marines, but when the recruiter told me that a Marine backpack would probably weigh about as much as I did at the time, I decided to join the Navy. The country was just coming out of the depression; we didn’t have much, and this was a chance to “see the world”—so we thought. I had to wait until age 18 because for the second time, my older sister Angie caught me trying to get my mother, who didn’t read English well, to sign my enlistment papers. The year before, I had tried to join the Civilian Conservation Corp. (CCC) to go off to Colorado, but Angie tore up those papers too.

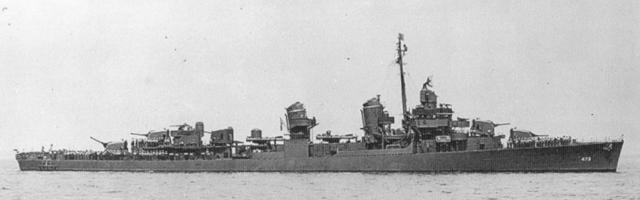

Our government lowered the draft age from 21 to 18 in November 1942, giving me more reason to enlist. I joined the Navy late in 1942, but it took until spring 1943 for a training camp opening to come up. In April 1943, right after basic training in Newport, R.I., I was one of 14 new boots ordered to Boston to report to the destroyer USS Bennett, DD 473, to complete her crew. I had never been on a ship before, or even seen a warship. This brand new ship was an impressive sight. At the time she seemed pretty big; around 375 feet long, and was rugged looking, with a lot of guns. She was one of the new Fletcher-class destroyers. Bennett had already been on her shakedown cruise, and she had many combat veterans from the previously sunken destroyers Duncan and O’Brien in place, including Commander Edmund Taylor and Lieutenant Commander Philip Hauck. I found out later that Taylor was awarded the Navy Cross and Hauck the Silver Star for heroism while commanding Duncan.

After a stop at Norfolk, VA, the scuttlebutt was that we were on our way to North Africa, but our orders had us turn south, and we escorted the new carrier Essex thru the Panama Canal to Pearl Harbor. At Pearl, Lt. Cdr. Hauck became commanding officer, relieving Commander Taylor.

We spent the summer of 1943 off Hawaii preparing for battle. I turned 19 and by now, I had my bunk and my sea legs. I was a seaman 2nd class. The food and the living conditions were about the same for everyone. My pay was about $50 a month, and I sent $40 of it home. It was about this time that the first of my two mess duty details came up. The ships’ crew took turns on this 3 month detail. Here’s where I met up with Johnny Austin, who became my good friend. We got assigned to the scullery. The boatswain’s mate in charge of the mess hall was Roy Boehm, another Duncan vet. Boehm later transferred off ship and then went on to a very distinguished career, becoming the first Navy Seal.

During general quarters (battle stations) I was assigned to the twin mount 40mm guns, which were fed with 4-shell clips. Bennett had several of these twin guns, several 20mm. guns, ten torpedoes, many depth charges, and five main guns, whose 5-inch shells weighed 54 lbs. and had about a 10 mile range. There was a lot of firepower. We fired at practice targets, and trained on our GQ stations. Unfortunately I saw some “green” fighter pilots from Essex crash into the sea during training exercises, and the carrier Enterprise transferred some veteran pilots to Essex so that Essex could join the Fleet. Later on, we got to live it up at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel for a few nights. It was a beautiful place. Then we left for the South Pacific, as a convoy escort, and crossed the equator on August 10, 1943. That meant that about 100 of us pollywogs had to become shellbacks after enduring the Navy’s traditional initiation tortures. Laliberte, the ship’s cook, had one eyebrow shaved off after seeing the Royal Barber. I was next in line and he ordered my left eyebrow shaved off. I had to go around for weeks without it while it grew back.

Back in trade school I was learning to be a machinist, and sometime after we crossed the equator, I got assigned to help out in the engineering division. (At the time, I was hoping to be a cook.) I got stationed in the #2 fireroom, which was located below the deck, right next to the rear stack. The #2 fireroom was unpopular because it housed the ships’ air compressor, which made loud hammering noises as it ran. I got to know the crew here, especially watertender 1st class Jarecki, and watertender 2nd class Snyder. (Only the last names of the crew were used aboard ship).

We went way down into the South Pacific, down near New Caledonia, and finished our convoy service. I thought this part of the world was beautiful. We got to see the most spectacular sunrises and sunsets, because whenever the ship was at sea, we were always ordered to precautionary general quarters just before sunrise and sunset. It was during these times that our warships were in the most danger from enemy submarines.

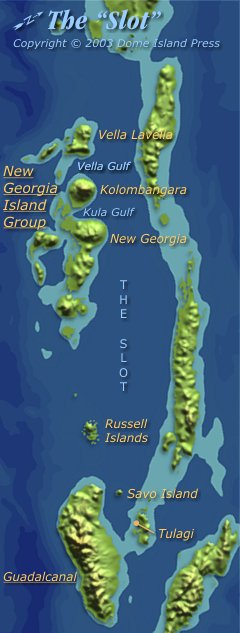

In looking back, we joined the war where the Japanese occupation had stopped, about 4,000 miles south of Japan. Their military had swept down and across the Pacific and occupied many island groups. The battle was over cutting off supply lines coming down from Japan, and then re-taking islands as our military forces moved north towards Japan. The islands were needed for air landing strips for our big bomber planes, which had a shorter range back then. We missed the invasion of Guadalcanal, but we got in on most of the other campaigns in that region.

The next day, we were off Bougainville Island. It was the morning after my first battle experience. I looked around, and I saw a destroyer, one just like our ship, lying dead in the water. The whole back end of what was the USS Foote had been blown off and was missing. I looked at that ship, and I said to myself, “I should be back in trade school . . .” Everything seemed different. I now knew what combat was like.

The conditions were very tough on all of us, but around this time, Snyder, who had been a Duncan vet, said something that I never forgot. His chance to transfer off the ship was coming up, but he said “Charlie, I’m going to ride this ship right to the bottom.” I knew what he meant. He was staying with Bennett no matter what, and from around that point on, so was I.

One day in early 1944, I sat down in the mess hall opposite about 15 heavily armed Marines. They said nothing, and neither did I, but I wondered how they got there. A few days later, we dropped them off at Green Island, north of Bougainville, for a surprise raid. The island was taken. We never did pick them up, nor did we find out what happened to them.

Sydney was a beautiful city, a wonderful liberty port. I made liberty with shipmates Kickler and Lamitola and we had steaks in nice restaurants and we visited a few nightclubs. I saw ‘Casablanca’ at a great movie theatre. Actually we were able to see a few movies aboard ship when we were in port occasionally, but it took the talents of our electrician’s mate 1st class Frank Hanratty to get the projector to work. We enjoyed the comfort of turned-over buckets for our seats up on deck. In the middle of one show, we got called out to sea and ended up chasing a Jap sub for two days. I don’t think we ever saw the ending of that movie.

Around this time, I passed a test and was promoted to fireman 1st class. By making this rate I formally joined the engineering division, and I got more duties in the #2 fireroom.

As part of the engineering division, if I wasn’t on watch I helped take on fuel while on the go from any ship (carrier, battleship, oiler) that had a supply. I had a lifeline tied on while the 1–2-hour refueling took place, due to the turbulence created by the huge ship that towered over us. Sometimes I got splashed with fuel oil, and there was a lot of deck cleaning to do.

At some point during this campaign, I had my GQ station changed to the #2 fireroom. At times we were at GQ for days on end, which meant that we got to dine on something called K-rations. This was packaged, mysterious food that came in a box, and it was served to us while we were at our battle stations. There was very little relief during this campaign.

We then went back to Guam and got in near its beaches, and gave extremely intense fire support for the invading Marines, while the battleship Pennsylvania’s huge shells were howling over our heads. Our gunnery crews got to be expert at rapid-firing our big guns. And they were accurate. Their skills were later needed at Iwo Jima. One thing I noticed: being stationed below during combat had a new effect on me. I didn’t get to see the action, which I suppose was good in a way. But the sounds were the thing: when I heard us fire the big guns, it was OK. When I heard us fire the 40 mm. AA’s, I knew we were getting closer. And when I heard us fire the 20 mm. machine guns, I knew what we were firing at was really close to us.

I believe that it was after this campaign that we had to go down near New Caledonia for eight days to get some work done on the boilers, and to replace some firebrick.

While we were coming back, we stopped somewhere near Éfaté Island, where we had a swim call. There was this tiny speck of an island, and this kind of beautiful, green lagoon. We were the only ship there. We dove and jumped off the ship everywhere, and the warm, crystal clear water was pretty deep, but I could still see all the way down to the bottom. It was easy to see the fish swimming around. This was, and still is, the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen. Who knew to take the ship there, I never found out. It must have been Commander Hauck.

Next we went down to the Admiralty Islands in preparation for the Philippine invasion, but the ship was ordered back to the States for an upgrade and overhaul.

When I got back to Bennett, half of the torpedoes had been removed to make room for more anti-aircraft guns, the quad 40mms. She also had some new radar detection equipment installed on the mast. This radar could detect enemy planes many miles away. A new crew of men, who I think were radar operators and combat air controllers, were also now on board. Bennett had been ordered to become a Fighter Direction Ship, with our own CAP (Combat Air Patrol). We were going to serve as a defense against a new weapon, the suicide plane (Kamikaze). The boilers got overhauled, too. It was about this time that I passed another test and made the rate of watertender 3rd class. This promotion further increased my duties in the #2 fireroom, and my pay soared to about $85 a month (I think). Snyder made water tender 1st class and was transferred to the #1 fireroom. He wanted me to transfer over there also, but our supervisor Jarecki said “no.” Jarecki, who was now chief water tender, said I was a good man on “the checks,” which involved monitoring the water level in the boilers.

We also got our hands on an ice cream maker and we got it into the mess area. I think we paid for it from the ships’ store kitty. We left the mainland for Pearl Harbor in mid December 1944 with a new commanding officer, J. McDonald, and our ice cream maker. Johnny Austin knew how to use it, and soon enough we were making ice cream, and I was eating it, lots of it!

In addition to providing fire support for our troops, we went around the island within range of enemy shore guns, trying to draw fire. There was nothing safe about this, but it was all to help our Marines. On March 1, one of the destroyers in our squadron, Terry, was hit with a heavy shell from a Jap shore battery. Tragically, my good friend from my hometown, Ray Roberts, was on that ship and he was killed, along with several other men. Ray and I had spent a lot of time reminiscing about our childhood when our two ships had been in port occasionally. We had played little league football on the same team, and it was really nice to have had a hometown friend out there.

Source: Larry Finn, USS Bennett.

Shipmate Dean Seiler with damage sustained from a dud aerial torpedo, 1 March 1945.

That same night, we got very lucky. Bennett was hit with a torpedo that failed to explode. It was dropped from a Jap Betty plane that we shot down after it flew over us. The torpedo could have blown the bow off. The dud made a hole up in front of the ship, and then it must have fallen out. The next morning we noticed water coming in, so we left for repairs, which took place in a drydock at Samar Island in the Philippines. As for the Marines on Iwo Jima, heavy fighting went on for weeks after that flag raising, until they took the rest of the island. The Japs would not surrender. There were no prisoners. And almost 7,000 Marines were killed there.

It seems we never stopped fighting off attacking planes over the next few days. After moving among several picket stations, we went south of Okinawa, to Kerama Retto, for supplies and ammunition. There were many ships there, a lot of them damaged. One destroyer was missing her entire superstructure. On April 6, we set off for Picket Station #4, and there were constant Kamikaze attacks that whole day. We kept moving up the picket stations, further and further north, closer to where the waves of Kamikazes were coming from. Near sunset we had a few very close calls, with one plane crashing just off our bow. I found out from our deck logs that we were ordered to Picket Station #2 to relieve DD Colhoun, which had gone to Picket Station #1 to assist DD Bush. Several Kamikazes had crashed into Bush and she was about to go down. Colhoun got to Bush and was giving assistance when she got hit several times also. Colhoun was disabled and was in danger of sinking. Bennett was then ordered to Picket Station #1 to assist both ships. Picket Station #1 was located directly between Okinawa and Japan. It was a very bad place to be on April 6, 1945. That was a terrible day for the U.S. Navy and our destroyers. I’ve learned that 13 destroyers were hit on that day alone.

Radar picket stations off Okinawa in relation to Kyushu. Click to view the picket stations in more detail.

We arrived at Picket Station #1 in the middle of the night. It was now April 7. Bush had gone down, and Colhoun was scuttled and sunk. DD Cassin Young had picked up most of the crews of both ships and then left with them. Bennett assumed charge of rescue operations, and we searched for survivors. Around dawn, a couple of Jap planes came in and we downed them. We continued to look for survivors. About two hours later, a pack of Kamikazes showed up. With our CAP and our own guns we shot down almost all of these planes, but one last Kamikaze that had been hit by gunfire many times and was on fire got through and hit us on the starboard side near the front stack, down around the waterline. The plane was carrying a 500-lb. bomb. It went through the thin side of the ship and exploded in the #1 fireroom. I heard the explosion, and I felt the ship rock back and forth. The blast ruptured steam lines, knocked out power, and damaged the #1 engine room, which contained the main generator. It also blew up a boiler. Yet some luck was with us because that boiler was not fired up. If it had been online, there could have been 600 lbs. of steam pressure built up, maybe containing enough force to split the ship open. When we got hit, I was on the checks in the #2 fireroom, which was around 50 feet from where the Kamikaze hit us.

I was told that Watertender 2nd class Sam Barbier fought through the steam to shut off the valves, getting burned doing it. Seawater was flooding in, and the ship slowed down. We were under Condition Red. More Kamikazes were expected. The guys got together and thought they could keep us going. Jarecki said they were going to transfer power to the #2 fireroom. Then Hanratty ran a thick black cable from the emergency generator up front, up across the deck, and then down to the rear engineering spaces, and he was able to rig it somehow to provide enough power to keep us going. I believe that their actions saved the ship and probably a lot of us, since those other 2 destroyers kept getting hit and went down after they got disabled. Sam Barbier was later awarded the Silver Star for his heroic action. The destroyer Sterett then arrived and screened us, and we returned to Kerama Retto under our own power, making it back on one engine, although we had no fire control over our guns.

Sadly, Johnny Austin was killed. So was Joe Martin, who I had gotten to know well during my second mess duty detail. 5 other men, all from our engineering division, were also killed, and a total of 14 more men were wounded, including Snyder. Most of the wounded men had been scalded by steam that may have been nearly 500 degrees F. They got medical help immediately from our doctor on board, and were later transferred to a hospital ship. When I went up top, I saw Lt. Sheridan get taken off ship, along with some other men. Some of them were covered with white stuff, which turned out to be asbestos. I can still see in my mind today how red Lt. Sheridan’s skin looked from the burns he suffered. I guess I was not meant to be in the #1 fireroom. Donelle, who was doing the same job as me in that fireroom, was killed.

We returned to Puget Sound Navy Yard when our leave was over, and as soon as Bennett was fully operational, we headed down the coast. It was now early August, 1945. We had our orders to head back to the Fleet for the invasion of Japan itself. Our military command was expecting as many as a million US casualties alone for this invasion. After what we had been through, and knowing that destroyers would be the first ships in on Japan, I felt like this was going to be “it” for us. Along with everybody else, I had no idea what an atom bomb was, but we were off the California coast when the atom bomb attacks on Japan took place. To my great surprise the Japanese surrendered soon after, and the war ended quickly, about two years sooner than I had figured. It was a tremendous relief.

I was ordered to stay at the Marines’ Camp Pendleton base near San Diego. This city was beautiful, and the weather was great. It was 70 degrees every day. Lots of servicemen were being released at the same time, and it took over a month until my name finally came up on a list that was posted every day. This meant that they had a way for me to get home. It was a train, again. Well I got my train and I took my third, and last, trip back east. At least this time I had a bunk. I had to go straight to Boston to get my discharge papers. After waiting there for a few days, I got discharged on March 11, 1946, and then I went home. I was 21 years old.

Evelyn and Charlie Greco in 2003.

In the end, Bennett got credited for participating in seven major engagements, and was awarded 9 battle stars in addition to the Navy Unit Commendation. The NUC honored our entire crew as a unit, and a bar was awarded to each member of the crew who was aboard ship at Okinawa on April 6–7, 1945. I learned that out of 175 Fletchers put into service, there were around 40 Unit Citations or Commendations awarded. Almost half of these awards were earned for service during Okinawa. Of the nine ships in our squadron, four were honored: Wadsworth was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, and Bennett, Anthony, and Hudson were awarded the Navy Unit Commendation.

The Navy records show that almost 5,000 sailors were killed at Okinawa, and more than 350 ships were damaged or sunk by the Kamikazes. I believe that it was the worst air-sea battle in U.S. Naval history. I also learned that 25 Fletchers went down during the war or were scrapped rather than repaired afterward—and around 72 destroyers in all were lost. It took me many years to find all this out.

As for Bennett, she was officially decommissioned in April 1946. I read that she was sold to Brazil in 1959, was in their navy for about 20 years, and then ended up getting used for target practice.

Well, these are my thoughts about things that happened when I was in the Navy, as I remember them. My children were asking me to do this, so I did it for them, and for my grandchildren. I’d like to thank my daughter Patricia for her inspiration, and my son Tom for his encouragement and his assistance in helping me write this down. Also, thanks to shipmates Larry Finn and Lt. Don Sheridan for jogging my memory of dates and places. And thanks to Dave McComb for maintaining a website to preserve the memory of the WW II destroyers and their crews.

And thanks most of all to all of my shipmates. It was an honor to serve with them.

Charlie Greco, WT3c, USS Bennett