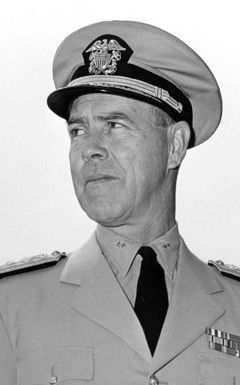

Above: RAdm. William M. Cole.

Below: RAdm. Joseph C. Wylie, Jr.

“At the Naval Academy, Wylie was ’brainy’, formal and correct, with a top-grade service reputation,” remembers then-midshipman Russell Crenshaw, Jr., who later served in Maury, in the van with Fletcher at Tassafaronga.

The first CIC was a joint invention of Cole and Wylie. In battle, rather than stationed at the after steering position as dictated by convention, Wylie’s station was the PPI [SG radar] scope (the 2,100-tonners were the first destroyers fitted with this equipment as built)—which let him see anything as it developed.

“Wylie stayed in that room on that scope, guiding us and calling out to Capt. Cole,” remembers Fred Gressard. “In the middle of the battle [of 12–13 November], Admiral Callaghan said ‘cease fire’, which was unbelievable. Then Cole said, ‘How do we get out of here?’ and Wylie gave him a course—they were always within earshot during battle; a great team. Afterwards, the CIC was adopted by the whole Navy.”

The aftermath of battle revealed the skipper as humanitarian. “I saw Juneau go up in smoke,” says Fred Gressard, “and a 5-inch mount came up through the smoke. The ship was gone when the smoke lifted. I couldn't believe there could be any survivors, but Capt. Cole wanted to turn back.”

“Turning back would’ve requiring disobeying orders,” remembers Crenshaw, “which would’ve been unthinkable.” Nonetheless, his decision not to do so apparently haunted Adm. Cole for the rest of his life.

“Then at Tassafaronga, [Admiral Wright] wouldn’t let us open fire. Afterward, Cole and the crew picked up more than 600 Northampton survivors, I don't know how they did it.”

Communications Officer Walter Sullivan was another fine officer, later Science Editor of the New York Times and first recipient of an award given since 1989 for Excellence in Science Journalism. Now known as the Sullivan Award in his honor, it is presented annually by the American Geophysical Union for reporting that makes geophysical science accessible and interesting to the general public.