|

| |||||||||||||||||

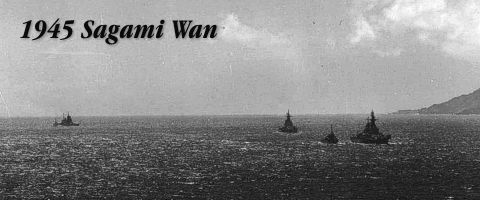

Nicholas (foreground) transfers pilots, emissaries and translators to Missouri off O Shima Island, approaching Sagami Wan, 27 August 1945.

On board Nicholas entering Sagami Wan

SAGAMI WAN, 27 August 1945 — Ira Allen, CWT of Los Angeles, CA, wore the same four leaf clover he had around his neck during the Battle of Kula Gulf. Dick Green, GM1/c was smoking the same briar pipe, and Joe Moll, SM1/c of Philipsburg, NJ, had even shined his shoes. It was

| |||||||||||

A few minutes after 0600 hours, the bridge lookout, Aime Morrisette of Fall River, MA, peered intently through his binoculars, and called over his shoulder, "Land ahead—off the port bow.” Soon the rest of us could see it, a shadowy mass behind the clouds on the horizon.

On the signal bridge, Thomas Connor, SM1/c of Evansville, IN, ran up the flag hoist and stared hard at his first view of Japan. His brother, a signal corps private captured on Bataan, was believed to be in a prison camp near Tokyo.

The task force formation began to break up. The battlewagons Missouri, Iowa and King George V dropped back. Cans and APDs moved forward, Nicholas in the lead. Three carrier torpedo bombers crossed overhead, flying very low, and disappeared into the haze beyond.

Nicholas was the lead ship in Admiral Bull Halsey’s Third Fleet, which was patrolling well at sea off Japan in July and August 1945, awaiting word to invade the Japanese home islands, an operation the 300 officers and crew knew would be their toughest fight of the Pacific war. — Doug Starr |

Now the Japanese ship was close at hand. She was a two-stack destroyer flying a huge Jap flag on the after mast. Nicholas’s skipper barked an order and the signalmen ran up a red and white flag. The Jap ship heaved to, rolling heavily in the swells. Her bottom looked as if it had a new coat of red paint. We could see her crew plainly. They wore green fatigues and high black boots. Carrier planes zoomed low across her decks.

Nicholas’s whaleboat move over toward her, the American flag on her stern standing out sharply against the blue water. Coxswain Lloyd Blakesley threw his tiller over and brought the boat smartly alongside the Jap. Bowman Leo Miles, S1/c of Homer, NY, passed up his new manila line and the Jap crew took it and held the boat alongside. Then things seemed to come to a halt. Officers and men in the whaleboat looked at the Japs; Japs crowded the rail and looked down. Nicholas’s skipper got impatient. Over the bullhorn came a sharp “What is the delay? Get them down in the boat!”

That seemed to break the deadlock. A whole mob of Japs emerged from the deckhouse and started crowding around the Jacobs ladder and sliding down into the boat. In a moment, Blakesley had a full load and started back to Nicholas. He came alongside, and the first Jap emissary climbed up the ladder and came on board Nicholas. He saluted the officer of the deck, who led the party to the wardroom.

The emissaries were a mixed group. Two who seemed to have the highest rank took seats at the head of the table in the middle of the room; the rest sat down around them and on a leather couch against the wall. The Jap faces seemed very alert and their eyes moved about the room looking at those of us who were in the room with them, and at the armed guards standing guard in the doorway. The two high-rankers wore gray-green Palm Beach uniforms with gold fourrageres around their shoulders. One had three rows of fruit salad on his left breast; the others had two rows. At the left hip both wore long swords that dragged on the deck, and they both wore short dagger-length pieces said to be known as “tanks.” One was from the Yokosuka Naval Base and the other was from the Tokyo Naval Department.

The commodore of the destroyer squadron came in and said, “Who is the interpreter?”

Two or three stood up and the commodore said, “Please tell your party it will be necessary to have them searched.”

One interpreter said, “We do not have any concealed weapons.”

The commodore said, “It will be necessary for you to remove your swords anyway.”

It seemed as if most of the group understood what he was talking about for they all stood and unbuckled their swords and laid them in a heap in the center of the table and then sat down again. For a moment the atmosphere seemed slightly strained and then everybody pulled out cigarettes and started smoking furiously. Photographers climbed on chairs to take pictures and the young pilots and interpreters watched with keen interest. A flash bulb popped, at which everybody jumped and then laughed. One Jap seemed greatly interested with the Silex coffee maker on the sideboard. He went over and examined it closely. Others found copies of Life Magazine and opened them eagerly. The first thing one spotted was a two-page spread of the B-29 runway on Guam. The Jap stared at it, moving his lips as if counting the planes line up on the runway in the picture. Another settled back to read with great concentration a war bond signed by Eisenhower, King and other chiefs of staff.

The whaleboat by now had made four trips, bring over a total of 13 pilots, two naval emissaries and six interpreters. Some of the interpreters were civilians. One was an oldish fellow wearing brown linen trousers, an old coat and a panama hat. Another was a young professor of ethics and philosophy at a college in Tokyo. He told me he had been a student at Columbia University in New York City in 1939.

Meanwhile, Nicholas was picking up speed. The executive officer came in and told the interpreters to tell the group we were going alongside the Missouri to transfer the naval emissaries. When this word was passed around, several got up and peered out of the portholes. The Missouri and the Iowa were clearly visible less than a mile away.

One of the Japs shook his head and smiled as if amazed. “Gee whiz,” he said, “they were new, yes?”

I told him they were a year old, and he shook his head again and went back to his porthole.

When we pulled alongside the “Big Moe,” she looked like Yankee Stadium on a summer Sunday afternoon. From the main deck to the mast lookout posts were was a solid mass of bluejackets and khaki uniforms. The vessel’s main battery of 16-inch guns was trained around—aimed point blank a O Shima, now only about ten miles away. Two huge American flags flew from the foretruck and gaff. On an open part of the bridge structure, surrounded by sailors, was a familiar figure wearing a baseball cap and sun glasses. Halsey, too, was out to see the show.

The line was passed over and back came a red chair fringed with white lace. Two Jap officers came out on deck. Sherman Meredith, BM1/c, motioned to one of them. The Jap stepped forward and sat bolt upright, a roll of harbor charts on his lap, a raincoat on one arm. Nicholas deck crew buckled him in. The boatswain pipe shrilled and up he went into the air like a staid private citizen riding a ferris wheel, not too happy about it but determined to maintain his dignity.

Suddenly a loud flurry of Japanese spouted from Nicholas’s bullhorn. The Jap destroyer had nosed in for a closer look at the proceedings and Nicholas‘s skipper had the Jap interpreter on the bridge order her to shove off. She did so reluctantly.

A few minutes later, orders were received to put the rest of the pilots and interpreters on other destroyers for transfer to various ships in the task force. Then, with Nicholas and the Missouri in the lead followed closely by the Iowa and the King George V and a screen of cans and APDs, the advance portion of the Third Fleet steamed swiftly into Sagami Wan, the lower entrance of Tokyo Bay. The Japanese coastline, at first a mere blur on the horizon, changed rapidly into a high rugged hill and narrow beaches fringed with villages. A few minutes after 1330 hours, the fleet heaved to and let go anchors. Off to port rose a huge bluish-gray mountain tipped with white. It looked vaguely familiar as indeed it should; it was Fujiyama.

— Evan Wylie CSp (PR) Yank Staff Correspondent.

Courtesy collection of Lloyd Blakesley

|