The Champion Kamikaze Killer

11 May 1945

by Capt. Doug Aitken, USN (Ret.)

At 0745 as I started to eat breakfast, the familiar GONG, GONG, GONG of the GQ bell sounded—again, with the expected announcement, “General Quarters, General Quarters, all hands man your battle stations.” But this announcement was different, however, as it was followed, breathlessly, by the words, “Commence Firing, Commence Firing, starboard side!”

Thus started a fateful day. Little did we know as we jumped again to our battle stations that after one hour and forty minutes the Hadley gunners would have amassed a total of twenty-three Kamikaze kills, including being hit by three; that nearly one-third of the crew would be listed as Killed in Action, or Wounded; and that “Abandon Ship” would be the order of the day.

Departing for the war zone from San Diego, Hadley was a brand new Sumner-class (692) 2,200-ton “tin-can” built at Terminal Island, San Pedro, CA, and commissioned on 25 November 1944. The captain, Commander Baron Joseph Mullaney, an Irishman, was a tough, battle-seasoned, and revered destroyer skipper who, a month after the battle, was promoted and transferred to command a destroyer squadron. We were fortunate to have had him to execute the high speed maneuvers necessary to keep clear of the diving Kamikazes, and give our gunners the best shooting chances. The crew was a composite of both new and battle-hardened sailors and officers who had been sunk in both Atlantic and Pacific. None, however, had ever faced the deluge of Kamikazes that we faced that day, 11 May 1945.

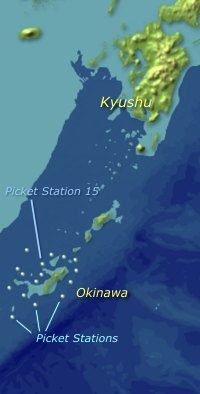

Radar Picket Station 15.

The intruder which called us to General Quarters was a single aircraft, a Japanese float plane flying very low on the water directly at us. It had escaped detection by both air and surface search radars, and also the Combat Air Patrol (CAP) of high flying Marine F4U Corsairs which we directed from our ship. Fortunately, our lookouts were alert, and our gunners shot it down close aboard. Everyone became intensely alert as we remained at GQ wondering what was next. All was quiet again for a few minutes. Then they came. A few at first—then a few more—then more. Finally came the hoards of them. The CAP shot down so many that they ran out of ammunition and forced some Kamikazes into the water by just riding them down. Others they chased away from our ships by forcing them upward. Those Marines in their F4U’s saved many of our lives.

Also at Radar Picket Station #15 was another destroyer, USS Evans (DD552), a Fletcher-class “Tin-Can” of 2,100 tons, which was experiencing equal problems. Accompanying the two destroyers were several smaller amphibious craft variously equipped to support landing operations: LSM(R) 193, and LCSs 82, 83, and 84, all sometimes jokingly referred to as “the pall-bearers.” We would soon learn to give them, and that term, a great deal of respect. ISM(R) 193 had a single 5-inch/38 mounted on her deck aft. When this gun was fired, the LSM(R) 193 suffered the likes of an earthquake estimated to be about 8.6 on the Richter Scale.

Without each other, surely neither of the two Destroyers would have remained afloat that day. An average of the estimates of the number of Kamikazes present by the CAP, by USS Hadley, by USS Evans, and by the “pall-bearers” indicated that about 150 Kamikazes had been in the sky above and around us. USS Evans, despite being hit early in the fight, did a credible job destroying 19 Kamikazes before being put out of action. USS Hadley suffered three hits: one was not serious; the second and third proved fatal. The second, at the waterline, opened up virtually all engineering spaces to the sea. A 550 lb bomb carried by that Kamikaze exploded directly under the ship humping the bottom nearly five feet as would a depth charge explosion. Moments later the third Kamikaze crashed the after deck house quad 40mm gun area with disastrous results. The multitude of problems caused by these hits resulted in total loss of power. Hadley was dead in the water, never again to sail under her own power, or fire a gun. Miraculously, the Kamikazes were gone. What happened to them we weren’t sure, but we didn’t much care at that point.

Hadley settled in the water, listed to starboard, her fantail awash, with fires and exploding ammunition above decks. According to all statistics, ship’s plans, and theories, Hadley was sinking, and the skipper’s immediate job was to get the wounded off, and to save all possible personnel. “Abandon Ship” was ordered and most personnel went into the water. Fortunately, it was not cold that day in the East China Sea. A number stayed aboard to fight fires and, in accordance with “the book,” to destroy coding machines, and properly dispose of classified documents. The injured and burned were taken aboard rafts, and their pain was eased by others who swam from raft to raft assuring that morphine was available.

With a streak of extreme pride, the skipper ordered the signalman to hoist all U.S. flags available, and anything else he could get up on the halyards and yelled, “If this ship is going down, she’s going with all flags flying.” A last great act of defiance.

LSM(R) 193 picked up many wounded and other swimmers and came alongside to Port, wired herself to Hadley, helped prevent capsizing, and transferred several pumps and hoses to fight fires. In the attempt to pump out some of the flooded spaces, it was not known, of course, that water was coming in through the bottom as fast as it was being pumped out the top. As LCS 83 assisted to Starboard, LSM(R) 193 made other short runs to pick up survivors and return them to Hadley. LCSVs 82 and 84 gave similar assistance to USS Evans which was having her own tough time.

About noon, LSM(R) 193 and LCS 83 began alongside towing of Hadley to the nearest anchorage, a small island named Ie Shima off the northwest side of Okinawa. USS Barber APD 57 came to assist and quickly took all seriously injured to the nearest hospital ship. LSM(R) 193 changed position to tow at Hadley’s bow as ATR 114 came alongside to continue pumping. USS Wadsworth (DD 516) approached to give assistance and firepower in case of further attack.

Thus, as we learned the hard way the job of the “pallbearers,” they earned our instant respect and grateful appreciation. With only a single 5”38 gun, and some 40mm’s among them, they also shot down some of the swarm.

The history of Hadley continues sadly as temporary patching was done to preserve the hulk, and she was towed to Kerama Retto (southwest of Okinawa) the repository of sick and wounded ships. (It should be noted that the Navy had more Destroyers sunk and damaged in the Okinawa campaign than in the rest of the war put together.) Hadley took her turn, eventually, in a floating drydock where the hull was drained and the real extent of the damage was determined. For whatever reason, it being July 1945, the hull was patched with plating, and a network of steel “I” beams was installed on the bottom to hold the ship together. Hadley, high and dry in the drydock, and well braced, was towed to the main anchorage at Okinawa (Buckner Bay) named for General Buckner who was killed in action on the island. Having been made seaworthy, Hadley floated out of the drydock, took on provisions, and with a reduced crew was taken in tow by a tug, ATA199, for the long trip home, via short stops at Saipan, Enewitok, and Pearl. We were towed into Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard at San Francisco on 26 September 1945, taking two days less than two months for the crossing. Roughly, it was 7000 miles at 7 knots—a long haul. The tow line parted nine times enroute but, thankfully, not while we wallowed in the fringes of a typhoon near Saipan where we tried only to maintain headway. We survived extreme rolls only because the center of gravity had been lowered materially due to several factors: heavy steel hull patches and “I” beams on the bottom, and removal of torpedoes, depth charges, and other ammunition and unnecessary topside weight.

After the Head of the Hull Board at NSY Hunter’s Point examined the engineering spaces on Hadley and climbed up through the hatch saying, “ . . . who the hell said they could repair this thing,” Hadley was stripped of all usable equipment, and decommissioned on 13 December 1945, a mere child of thirteen months.

When Commander Mullaney took command of Hadley in January 1945 at San Diego, he closed his remarks to the all-hands assemblage on the fantail by telling the enlisted personnel, “ . . . I’m going to have to learn how to get along with you.” And to the officers he said, “ . . . and you gentlemen are going to have to learn how to get along with me.” He did, and they did.

As evidence of the great respect which all members of the crew had for him, when the skipper was promoted and relieved at Okinawa on 18 June 1945, he instructed the Executive Officer not to tell the crew that he was departing at 0600 the following morning. That evening the Executive Officer visited the crew’s movie on the fantail, and announced quietly, “ . . . the skipper has ordered me not to advise the crew that he is leaving at 0600 in the morning,” and promptly returned to his stateroom.

At 0600 the following morning the rails were manned by a proud and tearful crew. Captain Mullaney had a twinkle in his eye as he waved goodbye.

In concluding his radio interview at Okinawa immediately after the famous battle Captain Mullaney said, “Destroyer men are good men, and my men are good destroyer men.” And so they were.

Various portions of the Hadley story, including its Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Crosses for both the captain and gunnery officer, and numerous other medals for crew members, have been published over the years in books, newspapers, and periodicals; and the Kamikaze 1 hour, 40 minute, air-sea battle record has stood unchallenged.

Near Chicago, commencing on 11 May 2005, the still-surviving shipmates of the USS Hugh W. Hadley (DD774), together with all available crew families, will gather to toast the Hadley, the Evans, LSM(R) 193, LCS 82, 83, and 84, the CAP of Marine fighter pilots, and all those who gave their lives at Radar Picket Station #15 exactly sixty years ago.