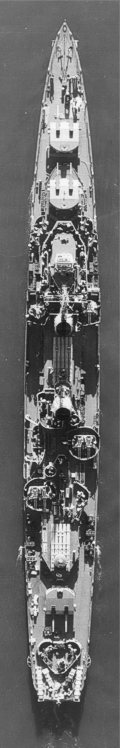

Statistics:

Standard Displacement: 2,200 tons.

Length overall: 376 ft. 6 in.

Beam: 40 ft. 10 in.

Speed: 35 knots plus.

Complement: 343 aboard at commissioning.

Armament

Six 5-inch/38 caliber dual-purpose guns.

Ten 21-inch torpedo tubes.

40mm and 20mm AA guns.

This vessel was commissioned on 25 November 1944, and Commander L C. Chamberlain, USN, assumed command. The nucleus crew of rated enlisted men was believed to be of an exceptionally high standard of excellence, and the roster of former destroyers on which these men had served would include most of the destroyers which had distinguished themselves during World War II.

Hadley reported to Commander Operational Training Command, Pacific, in San Diego, for shakedown on 23 December 1944. Training in all phases of anti-submarine warfare, torpedo firing, gunnery, amphibious warfare, engineering, communications, fighter direction, and damage control was supervised by Captain Glenn Roy Hartwig, USN, Commander Destroyer Squadron 66, the squadron to which Hadley was attached. He had shifted his flag to this ship, and remained aboard throughout the shakedown period. On 13 January, Commander Baron Joseph Mullaney, USN, relieved Commander Chamberlain as Commanding Officer. The final inspection took place on 5 February, and the ship was certified “very good” in all departments. Hadley was ready for combat.

Following a 14-day post-shakedown availability at the San Diego Naval Repair Base, Hadley left on 21 February 1945, took screening station on British escort carrier HMS Ranee (D-03), and escorted her to Pearl Harbor. Upon arrival, Hadley reported to Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, for further orders. On 7 March she proceeded as the single escort member of Task Unit 12.5.6 in company with USS Santee (CVE 29) enroute to Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands Group. The crossing took 12 days; then, 5 days were spent provisioning and taking on fuel and ammunition at Ulithi.

Under orders of the Commander 5th Fleet, Hadley left Ulithi on 25 March for Okinawa in company with Task Unit 53.3.2 consisting of many LSTs and escorts. The passage was without incident, and at 1650, 31 March, Takashiki Jima of the Okinawa group was sighted. The crew stood at General Quarters throughout that night as Japanese planes were reportedly active in the vicinity. Hadley fired at the enemy for the first time and drew her first blood by shooting down one of the harassing “Bettys” (Jap twin-engined bomber). None of the unit were damaged and the LSTs landed their troops on Okinawa Easter morning 1 April 1945. The task unit was dissolved on arrival, and Hadley was assigned as anti-submarine patrol station outside the transport area off Hagushi Beach. Low flying enemy planes again kept her at general quarters at night. After fueling at Kerama Retto, she reported to report to Commander Task Group 51.2 on the USS Ancon (AGC 4), patrolling in a retirement area east of Okinawa.

During the 4th day of this patrol, Task Group 5 1.2 was ordered to proceed to Saipan, arriving on 14 April. Enroute, Hadley had her first experience screening transports with fast and veteran destroyers, and also succeeded in exploding her first mine with machine gun fire. Six days later she was again underway for Okinawa in company with Task Unit 94.19.12, exploding another floating menace enroute.

On 27 April, Hadley arrived at Okinawa and was returned to the antisubmarine patrol station. The next day she was ordered to join Robert H. Smith, 2 LSMs and 4 LCS(L)s on radar picket station. She picked up a Marine pilot from the water after the engine of his F4U Corsair failed and he was forced to ditch. The first 2 days in May were restful, as the Okinawa area was blessed with an overcast making enemy air raids impractical; but blue skies brought the Japs back in force. Aaron Ward, predecessor to Hadley at the Terminal Island Shipbuilding Yards, was reported in sinking condition after absorbing 6 suicide plane hits in her unequal match on a picket station to the south of Hadley's position. The night of 3-4 May was not pleasant as several enemy raids from the north had the crew again at general quarters continuously during the seemingly endless night.

At sunrise, Hadley secured from general quarters; but at 0745 the crew raced to their battle stations to learn that Shea, 1,000 yards on the port quarter, had been hit by a Baka bomb and was burning badly. Hadley took control of their combat air patrol (CAP) until relieved 2 hours later by a fighter-direction equipped destroyer. When relieved, Hadley reported to Kerama Retto for logistics, after which she resumed station off Hagushi Beach. On 7 May, Hadley was directed alongside Brown, a veteran radar picket ship, for transfer of communication equipment from Brown to make Hadley a fully-equipped fighter direction ship. The job was completed in record time. Brown radio technicians were well aware of the significance that Brown was one of the few regulars who had survived the picket line.

Radar picket ships were scarce. At 1350, 10 May, Hadley took station with Evans as support ship. At 0636, 11 May a Jap plane was shot down by the CAP, but it proved to be only the forerunner of an estimated 150 planes which were approaching from the North. The CAP of 12 Marine F4U Corsairs soon had their hands full and, at 0750, an enemy observation plane was taken under fire and shot down close to Hadley. At about 0755 the entire CAP was ordered out in different formations to intercept and engage the horde of enemy planes closing. It was learned later that the CAP had destroyed about 40 or 50 planes. Hadley and Evans were attacked continuously by numerous enemy aircraft coming in groups of 4 to 6 on each ship. During the early period, enemy aircraft were sighted trying to pass the formation headed for Okinawa. These were flying extremely low on both bows and seemingly ignoring Hadley. The ship accounted for 4 of these. From 0830 to 0900 she was attacked by groups of planes coming in on both bows; she shot down 12 of these during this period by firing, at times, all guns in various directions. Evans was about 3 miles to the north, fighting off a number of planes by herself, several of which were seen to be destroyed. At 0900 Evans was hit and put out of action. At one time toward the close of the battle, when friendly planes were closing in to assist, the four support ships were prevented from shooting down two friendlies, which they had taken under fire. For 20 minutes Hadley fought off the enemy singlehanded. Finally, at 0920, 10 enemy planes which had surrounded Hadley attacked the ship simultaneously: 4 on the starboard bow under fire by the main battery and machine guns; 4 on the port bow under fire by forward machine guns; and 2 astern under fire by after machine guns. All 10 planes were destroyed in a remarkable fight, and each plane was definitely accounted for. As a result of this attack, Hadley was (1) hit by a bomb aft, (2) hit by a Baka bomb released from a low flying “Betty,” (3) struck by a suicide plane, aft, and (4) hit by a suicide plane in the rigging.

Hadley gunners were not the only ones whose ammunition was running low as more and more Jap planes splashed into the sea. Our Marines in their Corsair fighters overhead called by radio to say, " . . . we are out of ammunition, but we're not leaving the fight". One twin-engine Betty was forced into the sea by a Corsair which got above him and rode him down; another Corsair flew through a hail of shells from Hadley in an attempt to divert a Jap plane from a suicide dive. Twice he forced the Jap out of his dive, but even though the intrepid Marine flew almost into the muzzles of Hadley's guns he was unable to prevent the Jap, riddled from tail to prop, from hitting the ship.

By this time the ship was badly holed with both engine rooms and one fireroom flooding as the ship sealed down and listed rapidly. All 5-inch guns were out of action; a fire was raging aft of number two stack; ammunition was exploding; and the entire ship was engulfed in a thick black smoke which forced the crew to take safety, some by jumping over the side, others by crowding forward awaiting orders. The ship was helpless to defend herself and the situation appeared very dark. The Commanding Officer received reports from the Chief Engineer and Damage Control Officer which indicated that the main spaces were flooded and the ship was rapidly developing into a condition which would capsize her. The exploding ammunition and the raging fire were extremely dangerous. The engineers secured the forward boilers to prevent them from blowing up. The order, "prepare to abandon ship", was given and life rafts and floats were put over the side. A party of about 50 men and officers was organized to make a last fight to save the ship. The remainder of the crew and the wounded were put over into the water.

From this point on, a truly amazing, courageous, and efficient group of men and officers with utter disregard for their own personal safety approached the explosions and the fire with hoses, and for 15 minutes kept up this work. One officer fought the fire without shoes, on the blistering hot deck. Torpedoes were jettisoned, weights removed from the starboard side, and finally, the fire was extinguished and the list and flooding controlled, Although the ship was still in an extremely dangerous condition, one fireroom bulkhead held, and the ship was finally towed to the Ie Shima anchorage.

Today, Hadley proudly displays the 25 Japanese flags painted on her bridge, testifying to the number of enemy planes she destroyed. DD 774 established a record for destroyers in adding 23 of those flags to her scoreboard as a result of a single engagement. 28 of her crew died at their battle stations; 2 died soon after of injuries sustained; 68 others were injured. Not one of these men left his post of duty as the enemy planes came in, even after the ship had been hit and ammunition was running low. Examples of bravery and resourcefulness were continuous throughout the action.

The mission was accomplished. The transports at the Okinawa anchorage were saved from an attack by 156 enemy planes by the action in which Hadley took such a great part. She bore the brunt of the enemy strength and absorbed what they had to throw at her. It was a proud day for destroyer men.

Ammunition expended in this 1 hour, 40 minute battle: 801 rounds of 5-inch/38, 8,950 rounds of 40mm, 5,990 rounds of 20mm.

After noon on 11 May 1945, the groggy vessel was towed into Ie Shima where she stayed until considered in safe enough condition to be towed to Kerama Retto on 14 May.

There, in floating dry-dock ARD 28, the hard-working USS Zaniah ship-repair unit started patching, bracing, and strengthening the battered hull. A patch was secured to the hole in the starboard side where a suicide plane had .entered the engineering spaces, carrying delayed action bomb(s) which went through the ship's bottom, exploded, and broke upward a large portion of the after keel section. In the early morning hours of 19 June, the crew manned the rail to say goodbye to Captain Mullaney who had been relieved as Commanding Officer by Commander Roy A. Newton, USN.

On 15 July, Hadley, resting on the keel blocks of floating drydock ARD 28, was towed by ATF 150 from Kerarna Retto to Buckner Bay off eastern Okinawa. She was undocked 22 days later and again taken alongside Zaniah, this time in Buckner Bay.

The 6,800 mile voyage home at the end of a tow line began on 29 July when ATA 199 took her in tow and joined a slow convoy enroute to Saipan. The 3rd day underway, heavy seas and a violent wind verified radio reports that a 65 knot typhoon was being encountered. On 1 August, the ship rolled as far as 57 degrees to port, but the tow line held. The tow continued to Eniwetok, thence to Pearl Harbor where it was learned from Commander Destroyers, Pacific Fleet, that the ship was to be decommissioned upon arrival in the United States. Hadley and the ever-present ATA 199 left Pearl Harbor on the final leg of this trek on 12 September to arrive at U.S. Naval Shipyard Hunter's Point, San Francisco, California, on 26 September 1945. During the long, slow tow, taking nearly 2 months, the tow line had parted 9 times.

Thus was the USS Hugh W. Hadley entered on the roster of America's combatant ships as another fighting constituent of the United States Navy whose crew would not give up their ship. On 15 December 1945, Hadley was decommissioned. Following cannibalization for useful parts, she sold for scrap metal.

For the action at Okinawa, several medals were awarded to various officers and crew members, including Navy Crosses for both the Commanding Officer and the Gunnery Officer and, for all aboard, the USS Hadley was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, signed, for the President, by James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy.