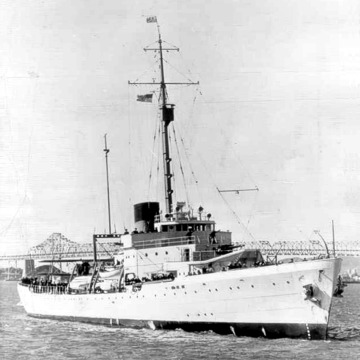

LOSS OF USS ALEXANDER HAMILTON (WPG 34)

[A half-hour before midnight on 23 January 1942], as Alexander Hamilton was making her way [to Iceland], the storeship Yukon (AF-9) suffered an engine casualty while en route to join convoy ON-57. Directed to the scene, the Coast Guard cutter arrived on the 25th and took the disabled “beef boat” in tow. The destroyer Gwin (DD-433) provided an escort, and the little convoy then crept toward Reykjavik at a snail’s pace.

By noon on the 29th, the three ships were only ten miles from their destination. The British tug Frisky put out from Reykjavik to take Yukon in tow, while the two escorts screened the operation. Alexander Hamilton then cast off the tow line and proceeded ahead, slowly, to keep clear of the tug and her charge, eight miles off Skaggi Point light, near the entrance to the swept channel to Reykjavik.

At 1312 on 29 January 1942, a torpedo from U-132—which had been patrolling off Reykjavik since 21 January—struck the cutter amidships without warning. One torpedo, of a four-torpedo spread, smashed into Alexander Hamilton’s starboard side, directly abeam of the stack. It hit the fireroom bulkhead and flooded the two largest compartments of the ship, blew up two boilers, exploded directly under the main electrical switchboard, demolished the starboard turbines and flooded the auxiliary engine room, and wrecked the auxiliary radio generator and emergency diesel generator as well.

The blast also destroyed three of the ship’s seven boats. The interior of the ship was plunged into darkness—no heat, steam, nor electricity remained.

While U-132 escaped the attention of nearby destroyers over the next several hours (she would ultimately reach La Pallice on 8 February and be sunk on 5 November 1942 by British planes) Alexander Hamilton settled lower in the water. Twenty-six men were killed instantly; six died later of the injuries sustained in the torpedoing. Ten more injured men required hospitalization. At 1345, eight officers and 75 enlisted men went over the side into the four remaining boats; Icelandic fishing trawlers then took these 81 men on board and carried them to Reykjavik.

With Alexander Hamilton down at the stern by some eight to ten feet by 1447, Gwin came alongside briefly to take off the last of the cutter’s crew, including her commanding officer, Comdr. Arthur G. Hall, USCG, who had ordered “abandon ship” when it became evident that, with the ship powerless and in imminent danger of being torpedoed a second time, nothing more could be done at that point.

That evening, the British tug Restive attempted to take the crippled cutter in tow, abandoning the effort after two hours due to the heavy seas. Brief consideration was given to having Gwin transfer a skeleton crew to Restive to attempt to board Alexander Hamilton but, again, the weather prompted abandonment of those plans. Throughout the night, Restive, Frisky, and the Coast Guard tug Redwing attempted to salvage the ship, but without success.

At 1015 the following day, the seas having moderated, Frisky took Alexander Hamilton in tow and, as the day wore on, progressed 18 miles. The cutter’s list increased rapidly to starboard, however, and she suddenly capsized at 1728 on 30 January 1942 at 64°32' north latitude, 22°58' west longitude. She remained afloat, though, bottom-up, and Ericsson (DD 440), which had arrived on the scene that morning to join the destroyer Livermore (DD 429) and seaplane tender Belknap (AVD 8) in escorting the salvage group, was then given the task of sinking the derelict. Three hits put Alexander Hamilton lower in the water, but she still remained defiantly afloat at nightfall, her hull barely awash. The cutter was reportedly still afloat that evening, prompting the dispatch of Ericsson to the scene, but the destroyer arrived the following morning to find only an oil slick.

Source: Naval History & Heritage Command DANFS and US Coast Guard.

Gwin completed shakedown training 25 April 1941 and underwent final alterations in the Boston Navy Yard before conducting neutrality patrol throughout the Caribbean Sea. On 28 September 1941 she assumed identical service in the North Atlantic from her base at Hvalfjordur, Iceland. After the infamous raid on Pearl Harbor, she hurried back to the Eastern Seaboard thence through the Panama Canal to San Francisco, Calif.

On 3 April 1942 Gwin stood out of San Francisco Bay as a unit of the escort for carrier Hornet who carried 16 Army B-25 bombers to be launched in a bombing raid on Tokyo. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey in carrier Enterprise rendezvoused with the task force off Midway, and Lt. Col. “Jimmy” Doolittle’s famed raiders launched the morning of 18 April when some 600 miles east of Tokyo. The task force made a rapid retirement to Pearl Harbor, then sped south 30 April 1942, hoping to assist carriers Yorktown and Lexington in the Battle of the Coral Sea. That battle concluded before the task force arrived, and Gwin returned to Pearl Harbor 21 May for day and night preparations to meet the Japanese in the crucial battle for Midway Atoll.

Gwin departed Pearl Harbor 23 May 1942 with Marine reinforcements for Midway and returned to port 1 June. Two days later she raced to join the Fast Carrier Task Force searching for the approaching Japanese Fleet off Midway. But the crucial battle was all but concluded by the time she arrived on the scene 5 June 1942. Four large Japanese aircraft carriers and a cruiser rested at the bottom of the sea along with some 250 enemy planes and a high percentage of Japan’s most highly trained and experienced carrier pilots. The Island of Midway was saved to become an important base for operations in the western Pacific. Likewise saved, was Hawaii, the great bastion from which attacks were carried into the South Pacific and Japan itself. But there were American losses too. Gwin sent a salvage party to assist in attempts to save carrier Yorktown (CV-5), heavily damaged by two bomb and two torpedo hits in the Battle of Midway. As attempts continued 6 June 1942, a Japanese submarine rocked Yorktown with torpedo hits and sank destroyer Hammann who was secured alongside the carrier. The salvage party had to abandon Yorktown and surviving men were rescued from the sea. The carrier capsized and sank the morning of 7 June 1942. Gwin carried 162 survivors of the two ships to Pearl Harbor, arriving 10 June 1942.

Gwin departed Pearl Harbor 15 July 1942 to operate in the screen of fast carriers who pounded Japanese installations, troop concentrations and supply dumps as Marines invaded Guadalcanal in the Solomons 7 August 1942. In the following months Gwin convoyed supply and troop reinforcements to Guadalcanal. Joining a cruiser-destroyer task force, she patrolled the “Slot” of water between the chain of Solomon Islands to intercept the “Tokyo Express” runs of enemy supply, troop and warships supporting Japanese bases in the Solomons.

On 13 November 1942, Gwin and three other destroyers formed with battleships Washington and South Dakota to intercept an enemy bombardment-transport force approaching the Solomons. The following night the task group found the enemy of Savo Island: battleship Kirishima, 4 cruisers, 11 destroyers, and 4 transports. The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was hot and furious. Gwin found herself in a private gun duel with cruiser Nagara and four destroyers. She took a shell hit in her engine room. Another shell struck her fantail and enemy torpedoes began to boil around the destroyers.

Though shaken by exploding depth charges Gwin continued to fire at the enemy as long as any remained within range. In a short time the other three American destroyers were out of action, two sinking and Benham surviving with her bow partially destroyed. But a masterful battleship duel fought by South Dakota and Washington wrecked Japanese battleship Kirishima. She had to be abandoned and scuttled as was Japanese destroyer Ayanami. The battle was over. The gallant American ships had saved Guadalcanal from a savage bombardment in this naval action that marked a turning point toward victory for U.S. forces in the Solomons.

Gwin attempted to escort the noseless Benham to Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides Islands. But when all hope was lost, survivors transferred to Gwin who hurried Benham’s abandoned hulk to the bottom with gunfire. The survivors were landed 20 November at Nouméa, New Caledonia, and Gwin was routed onward to Hawaii, thence to the Mare Island Navy Yard, arriving 19 December 1942.

Having been overhauled, Gwin returned to the Southwest Pacific 7 April 1943 to escort troop reinforcements and supplies throughout the Solomons. On 30 June she served with the massive amphibious assault force converging on New Georgia under the leadership of Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. She supported the most important landings 30 June on the north coast of Rendova Island, 5 miles across Blanche Channel from Munda.

Immediately after the first wave of troops hit Rendova Beach, Munda Island shore batteries opened fire on the four destroyers patrolling Blanche Channel. Gwin was straddled by the first salvo. A moment later a shell crashed her main deck aft, killing three men, wounding seven and stopped her after engine. The half-dozen enemy shore batteries were soon silenced as Gwin laid down an effective heavy smokescreen to protect the unloading transports. When aerial raiders appeared, her gunners shot down three. Rendova Island was soon in American possession. It served as an important motor torpedo boat base to harass Japanese barge lines and a base for air support in the Solomons.

Gwin escorted a reinforcement echelon from Guadalcanal to Rendova, then raced out in to the “Slot” 7 July to rescue 87 survivors of cruiser Helena, lost in the Battle of Kula Gulf. She then joined a cruiser-destroyer task force under Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth to head off a formidable “Tokyo Express” headed through the Solomon Islands to land troops at Vila. The battle was joined past midnight of 12–13 July and Japanese cruiser Jintsu quickly slid to the bottom, the victim of smothering gunfire and torpedo hits. But four Japanese destroyers, waiting for a calculated moment when Ainsworth’s formation would turn, launched 31 torpedoes at the American formation. His flagship Honolulu, cruiser St. Louis and Gwin, maneuvering to bring their main batteries to bear on the enemy, turned right into the path of the deadly “long lance” torpedoes. Both cruisers received damaging hits but survived. Gwin was not so fortunate. She received a torpedo hit amidships in her engine room and exploded in n burning white heat—a terrible sight. Destroyer Ralph Talbot took off Gwin’s crew after their heroic damage control efforts failed and she had to be scuttled. Two officers and 59 men perished with the gallant destroyer, casualties of the Battle of Kolombangara.

Gwin received five battle stars for service in World War II.

Naval History & Heritage Command including Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.