|

| ||||||||||

|

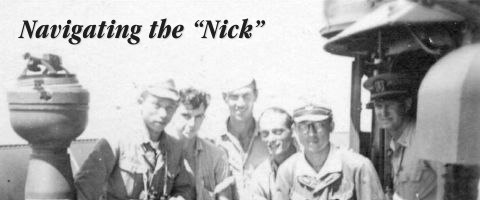

Courtesy R. D. Turpen collection

On the bridge of Nicholas, Sagami Wan, 27 August 1945: Japanese navigator and interpreter with bridge crew and author Doug Turpen at right. Click on the image above to view it in more detail.

|

The troop ship sailed to Nouméa, New Caledonia and unloaded. I was ordered aboard a fuel transport ship that was taking gasoline in drums to an air base on the main island of New Zealand. The ship took us from Nouméa down to New Zealand, and stopped at a rest and recreation area for fatigued Marine and Army personnel. They had a high-speed boat and fishing gear, and they lived in some cabins on the beach. They water-skied, fished and had fun for the two weeks they were allotted to be there.

That week the ship was unloading its several hundred barrels of airplane fuel. The fuel had to be transported up a winding steep road to get from the beach level to the airfield. George and I played with the guys on the beach and went water skiing and fishing.

The ship then went to Sydney, Australia, where we were supposed to meet the Nicholas. But by the time we got there, the Nicholas had gone somewhere else. It was a secret—they wouldn’t tell us. So we had a week in Sydney, bivouacked with an Australian family who were very nice to us, and then we had another week in Brisbane. We took the train from Sydney to Brisbane and saw a lot of the bush, complete with kangaroos and sheep.

We were assigned to stay for a week at the American Red Cross House, an R&R facility operated by American Red Cross women, and that was delightful. The house was on a beach called Surfer’s Paradise. We had a wonderful time there, surfing and partying.

Then we received orders to fly to Guadalcanal. It didn’t take very long for us to get there. The Nicholas wasn’t there either, but it was someplace near, so they flew us over to it and put us aboard.

NAVIGATOR!

I was delighted when I first saw the ship. I thought I knew what a destroyer was from my days aboard the Kilty, and then I saw this new ship. It was battle worn—it had been in a lot of action, which I knew. But I didn’t know too much more, because they hadn’t told us very much. I got the story from people on board after I got there.

I originally thought I was going to be Engineering Officer because my training was in electrical engineering. I had taken all the NROTC courses in engineering, running ship propulsion plants, electrical generators, switchboards and other equipment.

The captain had just promoted a Mustang (a Chief Petty Officer promoted to Ensign— “Okay, today you’re a Chief, tomorrow you’re an Ensign”), who was qualified only as an engineer. So he became Engineering Officer and I became a Deck Officer and Navigator.

My qualifications to be Navigator consisted only of my training in the NROTC. I knew how to take star sights, which I had done on the yacht off San Diego, and I knew how to calculate where we were using Bowditch tables and star charts. So I was a navigator—bingo!

The quartermaster, R.S. Lightsey, was truly a navigator. He really knew what he was doing. He could take the star sights, he could calculate and he could plot them. He could do everything I’d learned to do, probably better than I could. But I took the star sights from the time the Captain told me to do it.

TORPEDO OFFICER

I had been on board about two months, during which we were doing carrier guard and antisubmarine screen duty for a carrier group. Then the skipper called me one day and said, “We need you to be Torpedo Officer. What do you know about torpedoes?” I said, well, we had a little bit about them in school but not very much. And he said, “Okay, you’re going to torpedo school at Pearl Harbor.”

Orders were cut and I went to Guadalcanal—into a pool of people waiting for transportation back to the States. They put me on a ship with what was left of the First Marine Division, which was being sent home from Guadalcanal. They had been the main force taking Guadalcanal and their group was decimated. They had maybe 40 percent of their personnel to send home, many of them wounded.

I went aboard with the Marines as a result of meeting a doctor who was also going back to the States. He asked me, “Would you like to go to Hawaii through San Diego?” and I said, “Oh man, I got a wife in Los Angeles I’d love to see again!” He said, “Okay, I’ll take care of you.”

Aboard the ship, we passed within 20 miles of Hawaii as we went on to San Diego. So now I had to get into a transportation pool to return to Hawaii, which took another ten days. Marge met me and we stayed in La Jolla at the San Ysidro Inn just north of San Diego, a very lovely place, until I was ordered to leave on a plane for Hawaii.

Torpedo school lasted three weeks (through 20 August 1944). The school was eight hours a day in class and three or four hours in recreation around the island. The school was on Oahu, where we were able to see the surfing, Pearl Harbor, take a jeep out and scoot around where we wanted to go. It was a good school and a good experience in Hawaii. (Hawaii was not on alert at that time. The war was pretty far from there so we didn’t have real bad conditions, although they pretty much had a blackout.)

I also had a week of CIC [Combat Information Center, where targets are tracked by radar] watch training and a week of Loran training, then flew back to the ship were I resumed my assignment as Navigator and became Torpedo Officer.

By now, the ship was in the Gilbert Islands, where life aboard was not as stressful as it had been around Guadalcanal. Information was a little easier to get because CinCPac knew the location of every unit so when they had somebody to move, they moved him Johnny-on-the-spot to wherever he had to go.

From then through December 1945, I was on board ship except to get off on an island every once in a while.

DESDIV 41

Most of our duty was associated with carrier task forces, doing submarine screen and aircraft pilot recovery. Whenever we’d pick up a pilot, the carriers would send us a special thank you message. For every pilot we returned to a carrier, the carrier would send us enough ice cream to feed the entire crew as standard practice.

Other ships in the division included the O’Bannon and Taylor, plus various others assigned to give us a normal total of four ships. We were well known ships—we had good reputations throughout the Navy and we were already decorated. We got a lot of respect in the fleet because we’d been operating together a long time. All were smart ships—all had good captains and demonstrated good seamanship—we hardly ever had collisions!

ON THE BRIDGE

Life on the bridge as Navigator was an interesting affair on the Nicholas because the skipper insisted that I be on the bridge at any time the ship was in sight of land. (One would never guess, without seeing detailed charts, how many places there are where one could go “bump in the night” on such a vast ocean.) This was especially true around the Philippines and the other main islands groups, where we operated, starting with the return of MacArthur through Leyte Gulf.

We were in the second wave of the Leyte Gulf fleets bringing in supply ships and more firepower and so we anchored in San Pedro Bay and had a lot of activity in the Philippines. We were on the east side of the Philippines and a little north of Leyte Gulf and Surigao Strait. We were operating so much around the islands that I had to learn to sleep standing up leaning against the skipper’s chair. And that didn’t take me very long, because there were long days and nights when we were in the vicinity of the islands.

The squadron staff didn’t have a Navigator, so I navigated for the squadron as well as for the ship. The Squadron Commander didn’t speak to me directly—he was a Commodore and I was an Ensign (later a Lt. (jg)—it was almost an automatic promotion. If you didn’t screw up, you were promoted after a year). Rather, he interacted primarily with the Captain—the two of them were really close.

The Commodore would make the station assignments and tell the Captain where we were going. The Captain would call for a course to a new location. I got all my orders from the Captain—the Commodore’s staff also communicated his wishes to me, but I never really knew what we were doing until the Captain said “Give me a course to here,” normally followed by “Make it so.” Then whoever had the con would direct the helmsman, “half right rudder, come to course 182” and set the speed.

The Commodore was on the bridge at general quarters. I can’t remember where he slept. One of his staff bunked with me in the after-most stateroom in officer’s country, port side. And there were only two of us in that cabin.

The signalmen talked back and forth a lot between the ships in addition to sending official messages. Because I was on the bridge and had a quartermaster and a signalman for my immediate navigation duties, I was privy to a lot of the stuff the signalmen were talking about that nobody else heard.

Battle stations were called frequently because of the Japanese airplane activity and I was stationed on the bridge. As Torpedo Officer and Navigator, I spent all my time on the bridge. I never had watch duty any place else. Once in a while, I would stand as Deck Officer when we at anchor.

My recollection was that battle stations on the bridge included the Captain, the helmsman, the Executive Officer, the Commodore, his First Assistant, me, my quartermaster and signalman and a man on the engine control, which was a telegraph system to the engine compartment, to give them directions on speed and what to do for the ship’s maneuvering.

From my perspective, the Nicholas was a good ship and a smart ship. It performed all its assignments really well. Everybody on board was there to do his job, and there wasn’t any screwing around. There wasn’t any fighting on the ship. There wasn’t any of the normal stuff that happened on a lot of other ships where you had a lot of jealousy going on. Everybody worked together and the ship was sharp.

Captain Lyndon made that happen. He didn’t let anybody get out of line, which everybody knew, so they didn’t try, yet he was also delightful—always coming up with something funny and always cheerful, even under the most severe battle conditions we had to face, even around the Philippines when we first faced kamikazes. He was cool; he made his moves; he did what he did without being flustered and without getting excited. He was a great skipper and had a great sense of humor and a great rapport with the officers and all the men, and that’s one of the things that made the Nicholas such a fine ship to be on.

SHIPHANDLING

The ship had a fairly wide turning circle, so quite often we used our engines to assist in turning, particularly in the tighter waters of the islands. Engine speed was, for high-speed operation, around 400 rpm—below that we were loafing and above that we were at flank or better. I recall our absolute maximum was 37 knots and our ordered flank speed by the fleet was 35.

Our normal cruising with the fleet was between 20 and 25 knots. The carriers would crank up to 25 knots for launch and then would fall back for non-launch conditions, so we operated a lot around 20 or 22 knots, quite a bit at 30 and on some occasions 35 or higher if we could get there.

The ship was a smooth-running ship until about 30 knots. When you go above 30 and get up into 30-, 32- 35-knot ranges, everything starts to vibrate and shake and rattle and roll. In any kind of sea, 37 knots was not possible. But in smooth seas it would really crank up and roll.

The bow wave was incredible. I used to like to go forward as far as I could get which was right up to the bow and put a little lashing on the line so I’d stay there, and watch and feel the ship plunge through the seas. Once in a while, there’d be enough of a wave action to get water over the bow while I was there and that was pretty exciting. The Captain would make me come back when that happened, I couldn’t stay out there under those conditions. There were a lot of porpoise and a lot of activity ahead of the ship when we were at normal cruise, so that was part of the fun experience of being on the ship.

KAMIKAZE

The most dangerous and in a way thrilling part of the war activity occurred in Leyte Gulf when we began to have the kamikaze attacks. There were times when we’d have 40 or 50 ships in San Pedro Bay and Leyte Gulf, and we’d get a big wave of kamikazes coming in. All the ships would be firing antiaircraft fire. The damn Japanese planes would be diving on the ships and things were really in chaos when we had one of those big attacks.

The Nicholas had one kamikaze come close to destroying us. We could see this plane coming in, broad on the beam, flying probably 180-200 mph and headed directly for the ship. I was standing on the starboard side of the bridge with my back against the pilothouse structure watching this plane coming at me. It looked like it was going to hit me right on the nose. It was really coming straight in. Our gunners, we think, killed that pilot before he got to us.

All he would have had to do was tip that nose down a fraction and he would have been into the bridge or the first stack. If he’d hit us at the waterline at that position it probably would have taken the ship out completely. He went over the ship close enough to take off the top radar and a little piece of the mast. The plane crashed into the ocean 200 yards off the ship on the port side. It exploded when it hit the water, which meant that there were a couple of bombs on board that were quite sensitive. The debris we saw in the water after he blew up was the last we saw of that one, and we were happy about that.

TYPHOONS

While I was on board, we experienced three rather severe typhoons. We were at sea for all of them so that we were in the biggest water and the biggest wind and in all cases we were operating with a small fleet. I remember seeing one of the smaller carriers with the flight deck wrapped down around the bow of the ship. One ship was lost with all hands in one of the typhoons when the skipper tried to turn 180 degrees. He lost it in a full broach. The seas were so rough no one could attempt a rescue.

The waves were 30–40 feet high in the biggest typhoon. The bridge was 36 feet above the water and we were getting solid green water over the bridge, which meant that the waves had to be something like 40 feet or so in height.

Under those conditions, everyone was required to lash a safety line to themselves and some part of the ship whenever they were moving. In the biggest storms, everybody on board was carrying a bucket. I think there might have been a few without a bucket but I didn’t see them, however I never got seasick under all that pitch and roll.

Under heavy seas at any speed we had very erratic pitch and roll action so that it would tend to make anybody sensitive to motion really have it. Rolling, pitching, plunging, the deck would fall out from under you after you got on the crest of a wave and started down. If you walked, you would put a foot forward and you would find either the ship was falling away from where your foot wanted to go or was coming up to meet it, and it got to be really hard to move around in the heavy weather.

The Nick was a very seaworthy ship and we were able to batten down the hatches and keep it dry inside, although there were many times we had a five-foot wall of water rushing down the deck in heavy weather. Our speeds in those conditions were governed totally by the wave action and there were many engine changes because the skipper would want to power up a wave and power down the backside.

The engines were changing speed quite rapidly, but our engine crew was able to sense what was going on and so they were responding probably in advance of commands from the bridge to either increase or reduce power. The ship was a powerful ship. My recollection was it had two 35,000 hp Westinghouse steam turbine-driven props. This knowledge didn’t give me any comfort when I finally went to work for General Electric after the war. But they worked well. We didn’t really have any real engine room problems on that ship. Everything hung together; nothing fell apart. The engine room was able to keep it running pretty much all the time.

We steamed more than 230,000 miles before VJ Day. We recorded every day the distance traveled, and I’m sure somebody went through the logs and figured out what that number was. We had several very interesting actions while I was on board.

EN ROUTE TO LEYTE

We got orders in the middle of the night to proceed at flank speed to Leyte Gulf while we were operating with the carrier task force, 1,000 to 1,500 miles north of the Philippines. I was asleep in my bunk at midnight and somebody came down and shook me and said, “Captain wants you on the bridge.”

I said, “Whaat?” got up and went to the bridge, and he said, “I need, immediately, a course back to Leyte Gulf.” Lightsey and I conferred on the charts (we kept track of our movement almost hour by hour, so we knew pretty closely from dead reckoning during the night where we were at midnight): we looked at the chart and we looked at the currents and we looked at what we thought might be winds, and we selected a course of 182 degrees. We gave that to the Captain, so he turned the ship to that course and revved her up to flank speed and we took off like a shuddering banshee.

Fortunately the seas were modest and we could operate at maximum speed, which we did for two nights and one and a half days. We kept checking our position by star sight and by dead reckoning and the Captain kept asking, “Do you want me to change course?” and we kept saying, “No, hold your course.”

We steered that course, not in absolute manner but in fairly consistent manner, for the whole time it took us to get from our position at sea into Leyte Gulf. We made one turn into the entrance to Leyte Gulf. The ship did not change the helm’s course from the time we started until we made that turn. We went in and anchored at the north end of the gulf near San Pedro Bay, and when things quieted down, which they did for a day or so, the skipper called me in and said, “How did you do that?” And I said, “We navigated, sir!”

THE BATTLE OF SURIGAO STRAIT

We were called back to Leyte Gulf because of the impending Battle of Surigao Strait. We were in Leyte Gulf and the battle was imminent. Our ship’s assignment was to cruise on a rather hidden channel behind the entrance to Leyte Gulf—behind the entrance from the East—to intercept the Japanese force that was reported to be coming through that entrance from the North. That force consisted of some destroyers and cruisers, and was supposed to close up Leyte Gulf for the main Japanese fleet, which was coming through Surigao Strait from the south.

We were steaming at about 15 knots on a five-mile run in a narrow side channel, turning around and steaming back, waiting in case the Japanese fleet came toward that entrance. Our course was such that we would sail right across the main entrance channel if we kept on the same course as we moved north on this patrol.

Our orders were to launch all our torpedoes at the first ship. Our mission was “do and die”: if we’d had to make that attack, we probably would not have survived as a ship. So we were very lucky. They wanted us to sink a ship in that entrance because it wasn’t terribly deep and it would have been a real impediment to the oncoming Japanese.

As it turned out, the Japanese force came part way toward us but retired in the face of attack by a light carrier force that was operating to the north—the famous Battle off Samar. The carriers put a few of planes in the air and attacked the Japanese force. The Japanese commander thought it was just the scouting part of a large force, so he turned them around and went back north.

Our patrol was all at night and we saw all the fireworks of the Surigao Strait battle. There were battleships and cruisers and destroyers. The firepower that was used, and the number of shells and the light in the sky, was incredible. Most of that battle was fought at night so there wasn’t too much aircraft activity, but there was some. That battle broke the backbone of the Japanese fleet. We had really complete command of the seas after the Battle of Surigao Strait.

LUZON

Another action that we took part in was the recovery of Corregidor, which was a pitched ship-and-shore naval battle with heavy participation by our heavy ships. It was bombarded for several days. Shore batteries were firing at us but were effectively silenced. The paratroops were flown in wave after wave to secure The Rock. We eventually steamed into Manila Bay and went ashore. We took back Corregidor at some cost, but it was a higher cost to the Japanese.

Before and after Corregidor we were in Subic Bay for a period of time at anchor. The north bay at Leyte Gulf was San Pedro Bay. Subic Bay was on the west side of the Philippines, north of Leyte Gulf on the main island, and was a staging area for actions around the islands for a long time.

While we were there, we were at anchor a lot. We got to go on the beach and play baseball; we got to see the fortifications that had been placed there, which were many gun emplacements. None of them were in operating condition; they’d all been either bombed or shelled, so they were in really bad shape.

One really neat experience was the arrival of a hospital ship in Subic Bay. Our supply officer, Scotty, who was really a great guy, went over to the hospital ship and negotiated a beach party for the officers from our ship and the nurses from the hospital ship. We had a wonderful afternoon and evening with those nurses, and that’s something we’ll always remember because it was so much fun. They were very nice girls and we were all young bucks, so we had a good time with them.

ANTISUBMARINE

While we were on antisubmarine patrol around the islands, we sank, with a confirmed kill, one Japanese sub, and we claimed a strong possible second (later confirmed). On the confirmed kill submarine, we had debris, and a large quantity of oil came up after our depth charge runs—that was required if you claimed a kill.

All of those activities were recorded on the side of the gun director, which in our Nicholas book shows our final count, as far as the ship action was concerned. It shows aircraft, ships and submarines and the Presidential Unit Citation that the ship had received before I came on board.

We didn’t recover any personnel from the submarines that we attacked. I think their hulls were blown open by the depth charges and they sank with all hands from the point underwater where they were hit.

A depth charge attack is controlled from CIC and the bridge. The sonar men pick up the target. They calculated its course, speed and depth, and then a depth charge pattern is set up which would bracket the depth and tend to bracket their location in the direction of the submarine travel.

Depth charges should go ahead of, behind, and on either side of a submarine. We’d roll off six or eight from the stern and fire two or four from the launchers amidships on each side of the ship.

The ship took a pretty heavy pounding from the depth charges as they were exploding. It was always done at modest speed (20 knots) and then the speed was increased immediately after the launches to go as fast as we could go because we wanted to get the hell away from them. They were set to go off at an exact depth. There were men on the racks who did the setting, and the bridge controlled the actual drop. There were release controls on the bridge that were used to get precise timing. The bridge had to know precisely when those charges would go off, and usually the information was coming from CIC as to where we were, where the target was, and when we should drop. Those are pretty tight operations and usually were pretty well done.

TORPEDO

With respect to torpedoes, we never launched a torpedo in anger while I was on board. When we were in Subic Bay we took our squadron out for torpedo practice. A dummy warhead was loaded, which had flotation. At the end of the

|

We had three ships in this practice and one of my torpedoes was the only one that hit the target. It went directly under the target. It was interesting to find out later that the settings that I had given the torpedo man on the tubes, he had modified slightly. So we got a hit not on what I gave him, but on what he thought was right when he finally set it. We never told the Captain about the changed setting.

The practice torpedo is pictured in the web site. I did not fire any torpedoes except in practice, so it had to be a practice torpedo that was shown. Later on, around August, we started going north with the carrier task force. We did not participate in the battle at Iwo Jima but we were in the high seas nearby with the carrier group.

BORNEO

We participated in the recovery of the Tarakan, Borneo, loading port for fuel for the Japanese Navy. They had it heavily armored, heavily protected with troops, and it was a main source for their tankers to refuel.

We mounted a full-scale attack on Tarakan, which included several days of offshore bombardment by destroyers and cruisers, with a small carrier force to provide air cover. We steamed up and down outside the reef at Tarakan bombarding the shoreline, trying to seek out locations where the Japanese had gun emplacements to defend the port.

The entrance to the port was through a cut in the coral reef, 500 yards wide, and it was the only place for 20 miles on either side of this entrance where you could go across the coral. The coral was 10 feet under the water and it was a very large reef so any ship that didn’t make that entrance to Tarakan was going to be hung up on the coral and probably lose its hull. Only after entering this channel could we verify our position via radar contact on the Borneo coast.

We did our last day of bombardment and, in the late afternoon, the fleet turned and steamed directly away from Tarakan at fleet speed (20–25 knots). We steamed that way with zigzag courses until midnight, when the Nicholas had orders to return and lead the landing forces into this channel entrance to Tarakan Harbor.

We steamed back without zigzagging at 30–35 knots until we were close enough to the coral so that I should, as a navigator, be able to find that opening. We made one turn to the left as we came within 500 yards of the reef. We made one turn to the right and steamed into the cut, where we gained the expected radar contact. We were in the middle of the channel!

The landing forces were coming in behind us in LSTs and they were a mile off the reef when we hit the entrance. There was no gunfire from the Japanese. Either they didn’t pick us up or we destroyed their capability to detect us so that, as we went down the middle of the channel, the LSTs caught up with us and followed us in and made their landing.

The harbor was small but we had room to get in, turn and go back out after the landing ships came through. That’s what we did. When we got into quiet water again and things were quieted down, the skipper wanted to know “How’d you do that?” Lightsey and I looked at each other and laughed and I said, “We navigated!” And the result of that was a commendation for navigation, which came along later.

TOKYO BAY

When the day finally came to set up in Tokyo Bay for the surrender activities, we met the Japanese destroyer Hatsuzakura several miles out at sea. Japanese pilots and charts were taken from the Hatsuzakura to allow us to navigate through the extensive minefields that lay outside and in the entrance to Tokyo Bay. We took the Japanese on board from their destroyer under full General Quarters

|

The Nicholas was given the assignment to lead the Missouri and its accompanying destroyers and cruisers into Tokyo Bay. We had a thousand yard-wide channel, which was a fairly big channel but which required several turns, which were critical to getting through it without getting into some of the mines.

They had three kinds of mines indicated in their minefields. So it was a very dangerous place. The Captain asked me—with the Japanese on board and looking at their charts—if I could navigate from their charts. It was no problem because they had ranges on the land. We had Mount Fuji, we had a couple of other high points, which were both radar-indicated and visually indicated so we could take good bearings all the way through this fairly long channel. So I told him, “Yes, we can navigate on these charts.” He said “fine” and stood the Japanese navigators against the back of the bridge, put an armed guard on each side of them, and told them, “You guys stay there and shut up.”

Lightsey and I navigated the ship. We were really busy because of the course changes required to get through this maze and we had the entering fleet behind us. We made our way through this maze into the harbor, where the Missouri anchored and we anchored nearby. The other ships followed, so that we had probably 20–25 ships in Tokyo Bay surrounding the Missouri. We were very nervous about the Japanese because of their previous treachery and lack of honor in the war, so that it was a very critical two or three days before the ceremony.

SURRENDER, REPATRIATION AND HOME

On 2 September, we were given the duty of carrying dignitaries for the surrender ceremony from Yokohama Custom House Pier to the Missouri, and we have pictures, which I took, of almost all the people who came on our ship. Then we were anchored close enough to the Missouri so that we could see the signing ceremonies through our binoculars quite clearly. It was a real thrill to be there for the conclusion of the war with Japan.

Following the surrender, our ship was given the task of going north to Hokkaido to bring home prisoners of war. We made several trips doing that, and those men were given all the care that we could provide. Most of them had their wounds taken care of and their health restored. Many of them were flown home.

We left Tokyo Bay on 1 October and arrived in Seattle 19 October 1945. We had some duties to do after we left Tokyo, but they were minor and we steamed directly into Seattle. We spent a few days in Seattle and then steamed to San Francisco for a few days. I think the reason for doing that was to give the men a chance to see home again. Then we went to San Diego, and I was discharged 2 January 1946, from the discharge center at San Pedro.

AFTERWARD

I went to USC to interview possible employers. I decided go with General Electric in February. I reported to GE about the middle of February in Los Angeles and spent the next few months there because there was a long bitter strike and the plants were closed. I was transferred east as soon as the strikes were settled. I started in on the test program in Schenectady, New York about the middle of May 1946.

I was in the Naval Reserve and tried to join an active reserve unit in the Schenectady, Albany, or Troy area. There were so many returning at that time that all of the units were fully staffed. There was no place for me to be active. I resigned from the Reserve in 1953; thus I ended my career in the Navy.

|