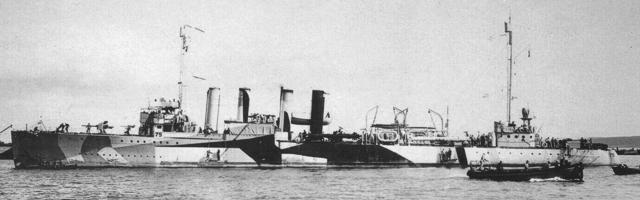

The Wickes class was funded beginning in fiscal year 1917. Fifty destroyers were to be built over a three-year period; twenty in the first year. Detail design was split between Bath Iron Works, which built the lead ship, Torpedo Boat Destroyer No. 75, and Bethlehem Steel.

The number grew to 61 (through Destroyer No. 135) when a Naval Emergency Fund, created on 3 March 1917, authorized “such additional Torpedo Boat Destroyers . . . as the President may direct.” Then, following a proposal of a special “Board on the Submarine Menace,” 200 more destroyers were added. A final twelve—through DD 347—were authorized in 1918 (together with 12 more destroyers, DDs 348–359, the first of which—Farragut—was not laid down until 14 years later). Of 273 mass-production flush-deckers thus ordered, DDs 200–206 were canceled, leaving 267 to join the six Caldwells in service.

The 111 Wickes-class ships were built in eight yards. (Some sources such as Bauer and Roberts classify only the 38 ships from Bath, Cramp, Mare Island Navy Yard and Charleston Navy Yard as the Wickes class—differentiating the 26 ships each from Bethlehem’s Fore River shipyard and Union Iron Works as the Little class, the 11 ships from Newport News as the Lamberton class and the ten ships from New York Shipbuilding as the Tattnall class.) As built, they proved satisfactory and greatly improved over the preceding 1000-tonners, but they exhibited three major shortcomings:

Thanks in part to the haste with which they were built—Mare Island, with advance planning, launched Ward in just 17 days—workmanship was inconsistent. Unlike the corresponding World War II period, there was no program to halt construction when hostilities ceased, so all ships ordered were completed. Then, because there were so many of them and so little need in the peaceful twenties, unusual measures were taken to keep them serviceable.

Surprises lay in store. When the Yarrow water-tube boilers on 60 Bethlehem-built ships wore out, they were set aside for scrapping en masse in 1930 while the Navy scrambled to recommission replacements from the “red lead fleet.”

Meanwhile, while the United States had not laid keels for any other destroyers during the ten years following 1922, other navies continued to build ships that incorporated lessons learned and technological advances. In 1932, therefore, when destroyer construction resumed, it was with ships so advanced and so seemingly lavish that they were nicknamed “goldplaters.”

This was not the end of the flush deckers, however. Those that survived the purge of 1930 found continuing roles. Some operated in secondary destroyer service, such as DesRon 29 in the far east. Some went to England and Canada in exchange for bases. Some even wound up in commercial service, e.g., transporting bananas between South America and New Orleans. But during World War II, many of them found valuable new roles—as conversions.