By chance, combat artist Dwight Shepler was an old New England skiing buddy of Emmons’ executive officer at Normandy (later CO) LCdr. Eugene Foss, USNR. Shepler, a Williams College alumnus and Foss, a Harvard graduate, had known one another before the war.

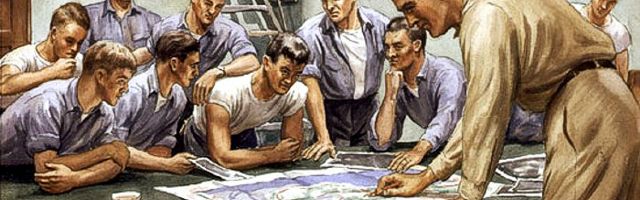

“Destroyer Gunners ‘Get the Word’” by Dwight Shepler #144, 1944: watercolor. The great moment has come for these men two days before D-Day, when a destroyer gunnery officer briefs his gun director crews and main battery gunners. In a sealed ship, the secret was unfolded along with exhaustive maps, drawings and photographs of bombardment targets. The men had to know their objectives well, for there would be no time for error when they came into point-blank range off the Normandy coast in the gathering light of D-Day’s early morning.

“Under the Enemy’s Nose” by Dwight Shepler #145, 1944, watercolor. Canadian 31st Mine Sweeper Flotilla, supported by DesRon 18 destroyers

Emmons and

Doyle, cleared a bombardment support lane to the Normandy coast during the night before H-Hour. The opening of the attack on Pointe-du-Hoc broke the tense silence in the diffused moonlight, while pathfinders dropped their red and green markers. Throughout these interminable hours of sweeping they expected all hell to break loose, but it never did.

“Opening the Attack” by Dwight Shepler #149, 1944. Watercolor. D-Day morning broke over the Normandy coast to find the elderly battleship Arkansas (BB 33), matriarch of the battle fleet, conscientiously banging away at the beachhead with her main battery guns. To seaward, French cruisers George Leygues and Montcalm, flying extremely large battle flags, sent shells hurtling into their captive homeland. Assault waves of landing craft streamed toward the beaches while attack transports filled the horizon. This was the way the “Arkie" was seen through binoculars from Emmons’ bridge at a bombardment station farther inshore.

“Target of Opportunity” by Dwight Shepler #150, 1944: watercolor showing Emmons dueling with a German 88mm battery on the cliffs above Port-en-Bissin, Normandy, Emmons’ primary target in the initial bombardment. Enemy salvos straddled Emmons which, with

Doyle, returned 5-inch and 40mm fire, silencing the enemy battery.

“The Battle for Fox Green Beach” by Dwight Shepler #146, 1944: oil on canvas showing

Emmons bombarding German positions covering the eastern sector of Omaha Beach, Normandy, 6 June 1944.

American forces fought all day for this stretch of Omaha beachhead. Its benign green bluffs and valley entrance were a maze of crossfire from enfilading German 88mm guns, mortars and machine guns, which raked the beaches and pinned down the infantry in a small area before expertly-placed minefields. By mid-afternoon, disabled landing craft were clogging the few gaps in the beach obstacles, while under a rain of short and long-range artillery fire, support waves circled and jockeyed for an opening. Destroyers moved toward the beach in shoal water to pump salvos of 5-inch shells into stubborn German emplacements and mobile targets of opportunity.

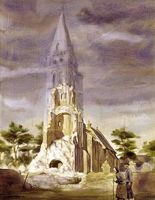

The house in the valley and the spire of Colleville-Sur-Mer’s Church of Notre Dame on the hill were landmarks of Fox Green Beach. Germans used the spire as an artillery control tower, with spotters able to see the full panorama of the American forces and direct artillery fire at opportune targets. The church’s lovely renaissance architecture crumbled into sad rubble when a US fire-control party on the beach called on Emmons to demolish it. It was this beach that Hemingway described in his article “Voyage to Victory.”

“The Tough Beach” by Dwight Shepler #147, 1944: watercolor. Omaha Beach was studded with obstacles, mines, pillboxes and fortifications. All day the landing waves suffered terrible attrition from enfilading German fire. LCI-93 called for help in bringing back the wounded; in response, a volunteer crew from Emmons went ashore in the ship’s whaleboat.

The house in the valley is the same one that appears in the previous painting.

“Usurper’s Watchtower” by Dwight Shepler #153, 1944: watercolor.

“Admiral Bryant sent word that Germans were spotting from the eleventh-century tower of the Colleville church; he wanted the tower knocked down without hurting the rest of the sacred edifice. That was a little too fine an order, even for Emmons. Her 12th shot was so near a miss as to shake the tower, and the 13th clipped it off obliquely a few yards above the arch of the west portal; part of the tower fell in the churchyard and part crushed in the nave.”

Happily, it was

rebuilt following the war.

It was no surprise, then, that as a combat artist who had already documented early action in the Pacific war, Shepler was assigned to cover the D-day invasion embarked in Emmons.

With his Kodak 35 camera to take the photos from which many of his paintings were derived, he documented preparation in England and the opening phases of the battle from Emmons, and later went ashore. The result was a large body of work, much of which may be found on the web in the Naval Historical Center’s collection The Invasion of Normandy.

Seven watercolors and oil on canvas works tell the story from Emmons’ perspective, from the preparation on board ship (top) to opening fire. The situation in doubt at Omaha Beach is well captured in scenes from both off and on the beach.

A key to the battle was the Church of Notre Dame at Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, with a lovely 11-12th century steeple, faintly visible in the fifth work presented here. RAdm. Bryant in Texas, commanding the bombardment group, sent word that Germans were using it as an observation post and wanted Emmons to take it out without hurting the rest of the church. Sharpshooting Emmons succeeded in doing so, but the memory of demolishing it haunted shipmates as artist Shepler captures in the final watercolor in this sequence. (Post-war, the steeple was rebuilt.)

« « «

Dwight Clark Shepler was born at Everett, Massachusetts and was graduated from Williams College in 1928, also studying at the Boston Museum School of Fine Art.

In May 1942 he received a commission in the Navy’s officer-artist program and soon saw combat in the South Pacific, initially from on board San Juan (CL 54) at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and then at Guadalcanal. In 1943, he went to England and in 1944 joined Emmons for the Normandy invasion, going ashore 11 June. With events fresh in his mind and captured on film, he went home to Massachusetts to prepare more detailed paintings, then returned to the Pacific. Embarked in DesRon 5 flagship Flusser, he observed the landings at Ormoc Bay and Lingayen Gulf and, from a PT boat, operations at Corregidor and Bataan. Again at home to finish the last of his more than 300 paintings plus two large murals for the U.S. Naval Academy, he retired from active duty with the rank of commander and was awarded the Bronze Star.

After the war, he continued his career painting landscapes, sports scenes and portraits in watercolor as well as commercial illustrations and advertisements. He also remained active as an educator and was President of the Guild of Boston Artists. He he died in 1974.

Many of his works are represented in the Naval Historical Center’s on-line collection.